Bach is a Strange Loop

Prelude

Every night, ten-year-old J.S. Bach reached his little fingers through a locked bookshelf with a latticed front, rolled up a book of sheet music inside, drew it out, and copied it by moonlight, for he was not allowed a candle. It took six months for him to finish this difficult endeavor, only for the copied manuscript to be found by his older brother and taken away.

This was a child who had music pouring into and out of his ears since before he could talk. As little as we know about his life story, this fact is undeniable. Something was going on inside his head, strongly, forever. So does it make sense to look at his life in terms of events, or something more, something equally internal?

Allemande

Even if you hate classical music, you’ve heard Bach’s six cello suites. At least, the prelude of the first suite, in movies and on television. Like in Master and Commander and Family Guy and The Hangover Part II. And in this American Express commercial showcasing household objects making frowny faces and smiley faces. In fact, it’s often heard in commercials advertising financial services. “In the case of recent television commercials, Bach has more or less taken on a single function: reassurance,” said musicologist Peter Kupfer. “It is no coincidence that most companies that use Bach in their commercials offer financial or insurance services (including American Express, MetLife, and Allstate), thus requiring a message of trust.”

Courante

Can you call yourself a mathematician if you haven’t read Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid? Can you call yourself a former math major if you haven’t given up on that and read Hofstadter’s easier follow-up I Am A Strange Loop instead? Both books are about how math connects to the mind, how something arises from nothing. That something being: consciousness, ensoulment. That unexplainable, undeniable thing in all of us.

The way this happens, Hofstadter tells us, is through recursion. Recursion is different from repetition. It requires self-reference. I am able to think about “I” and also able to think about thinking about it and maybe, if I stretch my brain muscles very hard, I’m even able to think about thoughts about thinking about it.

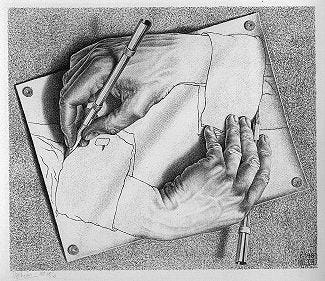

The simple idea is the world contains many recursive loops that are worth examining. It has to be a recursive loop that both somehow reaches higher than itself while staying on the same plane. This, according to Hofstadter, is the definition of consciousness. To reach this conclusion, he invokes number theory and philosophy, including meditations on Bach, as well as images from M.C. Escher, like that of the hands drawing one another into existence—in the image below, there is a “drawer” and a “drawee” and the drawer is on a higher level than the drawee and yet they constantly come back to each other. A thinker thinking about oneself is, by definition, bigger than the thing they are thinking about, but because that is impossible, they must compress their idea of “me-ness” into something smaller and more compact, even though they are one and the same.

Sarabande

Johann Sebastian Bach’s mother died when he was nine years old, his father when he was ten. Later, he married a beautiful woman and then she died young from a quick and unexpected illness. He himself fathered twenty children, ten of which died before adulthood.

Deaths like these were relatively common in those days. Illness had no answer. Childbirth was more dangerous than war. His father was similarly orphaned by age ten.

This father, by the way, had an identical twin and, the story goes, the two of them looked so similar their wives would mistake them. They composed together, played together, grew ill together. When his father’s twin brother died, the father died shortly after.

Minuet I / II

Bach’s music often doubles back on itself, refers to itself, grows bigger while remaining the same. There are six cello suites in all, each composed of six movements. An introductory prelude that introduces a key and an idea, veering on improvisational, with no repeats. Then various dances that come from many different nations. First is the German “Allemande,” which literally means German, a serious dance in 4/4 time. A flowing “Courante,” a French word, a flowing dance in triple meter. The “Sarabande” is next, a Germanified version of the Spanish “zarabanda,” a slow and solemn tune, what some call the heart of each piece. What follows is either a Minuet or a Bourree or a Gavotte, all French words, all fast and upbeat dances in two parts. And it ends with a “Gigue,” which I don’t have to tell you is an Irish jig, which is always leaping and extravagant and fun, even in a moody minor key, and often brings in reminders of the suite’s prelude, closing the loop.

Gigue

But how true is the moonlight copying story? According to the world’s most boring biographer—Christoph Wolff—probably not true at all. It came from the writings of Johann Nikolaus Forkel (another Johann!), who interviewed Bach’s sons when putting together the first real biography of Bach in the early 1800s. But as Wolff points out, Forkel had a habit of embellishing his anecdotes, and besides, where was this mysterious manuscript Bach had so daringly created based on a copy of his brother’s? Why was it never found, even with the brother?

But why would Forkel lie? Because he was absolutely obsessed with Bach and the idea of Bach as a genius. Forkel wrote in the introduction to his biography:

“This man, the greatest orator-poet that ever addressed the world in the language of music, was a German! Let Germany be proud of him! Yes, proud of him, but worthy of him too!”

Forkel wanted to position Bach as a singular genius, in service of a great Romantic project to create a strong national German identity. Forkel turned Bach from a man into a hero. So of course, it makes sense he’d want to strengthen the claim with an origin story, true or false, about a child so struck by the need to learn and create music that he disobeys his brother; t a story of a genius child struck by the divine.

Prelude

In 1730, when Bach was teaching at Leipzig and was displeased with one of his bassoon players, he called him a “nanny-goat.” Later, the bassoonist confronted Bach on the street with a large stick and called him a “dirty dog,” to which Bach responded by pulling out his sword, and a swordfight ensued.

This story is confirmed by church court records. Although it’s unclear who insulted whom first, and it was more of a dagger than a sword, and really they didn’t even slash their épées, it was more of a wrestle. Still. This was a man willing to fight over the integrity of his music. And who knows? Maybe the bassoonist really was a nanny-goat. The records don’t say.

Allemande

For a long time, no one heard of the suites. In fact, most of Bach’s compositions were lost. They were used as cheese wrappers and for padding fruit trees.

Then, 150 years after Bach died, a 13-year-old cello prodigy named Pablo Casals came across the Suite manuscripts in a second-hand music shop in Barcelona. The shopowner didn’t think they were anything special. Little Pablo saw stars. He purchased the music for a pittance, and practiced the suites for ten years before ever playing them in public.

He then devoted the rest of his life to touring the world and popularizing them. One girlfriend of his—a young cellist—said she would never play the Bach Suites in public, because they were Pablo’s. They broke up not long after. He married an opera singer.

Courante

The brain is a pile of flesh full of neurons that, on an individual level, signify nothing. The world is made of subatomic particles that, people say, cause things to happen. Hofstadter disagrees: he thinks the only things worth looking at are bigger categories. This is the level we live in, Hofstadter says—so far zoomed out from our individual atoms that we can’t see them, and even if we could conceptually understand them, that knowledge would still have no bearing on our actions. Yes, one could say that the reason I get up to go to the bathroom is the result of a million tiny neural actors. One could say the same of war: it’s no one’s fault, it’s physics. And yet we all know it’s wrong to say so. We evolved to create categories and symbols, to make sense of the big buzzing brightness of the bajillion sensory inputs we take in at any given moment. So now we live in a world filled with and made of symbols. There is no other way to live.

We are not unique in forming categories and symbols. A plant, for instance, will never grasp atomic theory, but it can “recognize” sun and water and reach towards them both. The crucial leap comes when one of the categories we recognize is: “myself.”

Sarabande

Johann Sebastian’s father was named Johann Ambrosius Bach. Johann Ambrosius Bach had a twin brother named Johann Christoph Bach. Johann Sebastian’s siblings were named Johann Rudolphus, Johann Christoph, Johann Balthasar, Johann Jonas, Johann Jakob, Johanna Judith, and Maria Salome (named after her mother). Johann Sebastian Bach himself had five Johann sons, (one named Johann Christoph, the same name as Bach’s uncle, first cousin, and oldest brother), and one Johanna daughter. Only six of twenty total children; that ratio is much smaller than that in his own generation, but even so, every moment must have been like living in an aural mirror, a perpetual echo. Johann! Johann! Johann! Yes? No, the other one!

Of course, this isn’t right, because most of the Johanns simply went by their middle name. The hero of our story went by Sebastian, which comes from the Greek word for “venerable” and is based on the root word for “awe, reverence, dread.”

Even so: Johanns were everywhere. Everywhere.

Minuet I / II

Music is the sound of nature, and music is made of math. There are numbers on a scale, numbers in a meter, and each can be identified and assigned meaning. Fast and slow and always moving forward. Numbers add up something shifting, tectonically, in your heart as you listen. Numbers take you through time from one place to another, the beginning of a song to the end of one.

The solo cello was a strange choice for music in Bach’s age. It’s still strange. It’s a melodic instrument, meaning that, for the most part, only one note can be played at a time. As opposed to a harmonic instrument, like the piano, where multiple notes can be played at once to create chords and a background sound. Sure, sometimes two notes are played in a double-stop, but even that isn’t enough for a chord, for which you need three.

Yet the suites feel full of harmony. How? Eric Siblin writes in his book The Cello Suites: J.S. Bach, Pablo Casals, and the Search for a Baroque Masterpiece, “He removes as many notes as possible to strip the polyphony down to its bare essentials and let the listener fill in the blanks. He alternates fragments of different lines from different registers and tricks the listener into thinking he or she is hearing more than one line at the same time. Bach implies harmony.” Something exists in the air, even if it can’t be seen or truly heard.

Gigue

Romanticism is about sublimation of the soul. Romanticism follows the individual to the ends of the earth until they barely exist any longer. Romanticism allows you to stare into the depths of the earth and say: this is also me. Romanticism makes you stop thinking at all.

So it makes sense that Romanticists would try to sublimate themselves into a larger, more amorphous identity, tied to the idea of a nation. The “essence” of a nation finding a home in each of its individuals. And this individuality still creating a ground-up idea of a nation. What is France without French men? What is Germany without Bach? Forkel wrote:

“Bach’s works are a priceless national patrimony; no other nation possesses a treasure comparable to it. Their publication in an authoritative text will be a national service and raise an imperishable monument to the composer himself. All who hold Germany dear are bound in honour to promote the undertaking to the utmost of their power. I deem it a duty to remind the public of this obligation and to kindle interest in it in every true German heart.”

Prelude

Bach once spent four weeks in jail. He was concertmaster in the Weimar court but wanted to leave his position early to accept a more prestigious one under Prince Leopold in Köthen, sixty miles away. But he was still legally bound to his position in Weimar, and the Duke did not consent to Bach’s early termination. It was considered a breach of contract, and also, pretty embarrassing for the Duke. So he sent Bach to a “justice room” for four weeks before the Duke let him go with an unfavorable dismissal.

Allemande

Serious cellists can spend their entire lives studying and playing Bach’s six cello suites. And many have. Yo-Yo Ma, the superstar of the cello world, and possibly the classical music world at large, recorded the suites three different times at different stages of his life. His first recording, made when he was in his twenties, was done with an “I know everything” attitude (in his words). In the second recording, he said, “middle-aged confusion” abounded. The third recording was just right. He toured the world like a rockstar to share the suites with people around the globe. He reached every continent except Antarctica, although he’s not dead yet.

Courante

Sometimes I can think about thoughts about thinking about “I,” but for me the buck stops there, that’s my limit. Could there theoretically be a creature with even more levels of abstraction, to think about thinking about thoughts about thinking about “I”? If so, would their consciousness be somehow bigger than ours? Is it a spectrum?

Hofstadter says yes. He believes there are different levels of consciousness, or what he calls “souledness”—the amount of “soul” one has or is capable of. He posits it could theoretically be quantified and mosquitos would be about at the bottom rung. He really, really hates mosquitos.

Sarabande

Why was Bach so stubborn in trying to leave the Weimar court? We have no letters from him providing an explanation. But many biographers paint a picture of a restless, roving, Romantic mind. They say the Weimar court duke was rigid and controlling over the type of music played, requiring Bach to compose within the narrow constraints of the Lutheran liturgy.

Prince Leopold was a world apart. He was a deep lover of music, and a trained musician himself. He traveled the continent to see opera in Italy and Austria and more. He oversaw a Calvinist court, yet despite Calvinism’s usual austerity, he invested heavily in his orchestra. Prince Leopold loved music, it seems, and loved Bach, and wanted to let him loose in his compositions, allowing Bach to be as inventive and secular as he liked, as long as he composed with beauty, which, Bach being Bach, was always the case.

Bourrée I / II

The original manuscripts for the cello suites did not survive, but two early copies were made, one by Bach’s second wife, Anna Magdalena, and the other by an organist named Johann Peter Kellner. The two copies disagree with each other about bowings and phrases, and neither have very many dynamic or articulation markings (which notate how loud or soft one should play, how languid or forceful or light).

This means the individual cellist has a lot of leeway in their interpretation. That’s their right. It is common to make each note pour into the next one as if they are all connected, like the flow of a waterfall. But in some recordings, Yo-Yo Ma gets a little weird. Adding too-long emphases and strange pauses and short stutters. That’s okay. It’s Yo-Yo Ma. Yo-Yo Ma can do whatever Yo-Yo Ma wants. In Yo-Yo Ma’s hands, the songs still breathe. They are still alive. Perhaps more so.

Gigue

Romantic composers deeply admired Bach, especially Felix Mendelssohn, who was, the story goes, responsible for reviving him. In 1829 in Berlin, Mendelssohn conducted a performance of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, the first since Bach’s death. In the preceding years, he was looked down upon as too academic, too rigid, with not enough feeling. Mendelssohn showed that no, Bach’s music is full of feeling, it lays the groundwork for feeling. It is the foundation on which the mountain sits to reach towards the sky. German Romantic composer Johannes (yes another Johann, but more formal!) Brahms once said, “Study Bach, there you will find everything.”

Prelude

Hofstadter loves Bach. But that doesn’t mean he loves every rendition of Bach. After he first fell in love with Bach, he sought every Bach record he could find:

“I soon discovered something that troubled me, which was that many performers took them very swiftly and jauntily, as if they were merely virtuoso exercises as opposed to profound statements about the human condition.”

Allemande

It’s unclear when exactly Bach composed the cello suites, but scholars conjecture that he wrote them between 1717 and 1723, during his years as concertmaster at the Köthen court under Prince Leopold. This is when Bach had the most freedom to write solo pieces for individual instruments, which he did, for the cello and violin and harpsichord and lute.

Courante

What separates “me” from “you?” Or even “me” from “not me?” The answer, Hofstadter argues, is not so simple. On an atomic level, I am eating, breathing, drinking, listening, perceiving, and everything I consume becomes part of me. Even the difference between “skin” and “not-skin” isn’t as clear-cut as we might think; atoms and molecules are in constant motion, drifting, shedding, and mingling across the line. The body has no hard borders.

Can our souls cross-contaminate with our surroundings and with each other? Particularly in ones we love. If I am in love with you, you also get subsumed into me, because our patterns begin to match, and I see the world with the same categories. I start to see the world with your eyes. I can watch a video of kittens and say, “my love would love this.”

Sarabande

During the time period in which Bach most likely wrote the suites, his first wife died. It was an unexpected death. Bach was away for the summer at a spa town with Prince Leopold. When he got back, his wife was dead. There are no reasons provided.

Bourrée I / II

In his second recording, Yo-Yo Ma released short films to go with each suite called “Inspired by Bach.” Each film showcases the suite’s mood. They explore architecture, drama, relationships, choreography, ice skating, and gardens. The first suite goes with “The Music Garden,” in which Ma recruited an architect to help him design a garden based on the suite. They tried to build it in Boston’s City Hall Plaza, but were unsuccessful. The city officials said Ma’s demands were “unreasonable.” Instead the city of Toronto stepped in. Now anyone can visit the “Toronto Music Garden,” with riverscapes and trails intended to invoke the first suite.

First there was music: waves in the consciousness of a man who lived centuries ago, then simple vibrations in the air. Now there is a three-acre garden in Canada. Something, from nothing, if music can be called nothing.

Gigue

“Music owes as much to Bach as religion to its founder,” said Schumann, another famous Romantic composer. Religion and Romanticism have an uneasy alliance. Romanticists often pushed back against the rigid constraints of the Church. And yet they were all trying to access the divine, and most still believed in God.

Likewise, many religious sects that focused on the individual, like several major branches of Protestantism, tended to eschew music. And yet they have much in common with the Romantic composers, who similarly wanted to engender that sense of ensouledness from withinthe individual as they reach for the divine.

But how does a movement so focused on the individual transcend itself? To call it a “movement” requires a large group of people trying to move society in one way or another. These days we have several people thinking and talking about a “neoromanticist” movement online. This was a pleasant surprise to me, an unknown writer who has never been part of any “scene,” because a year and a half ago, after a deep consideration of where my work might fit into the literary canon, (a self-indulgent thought experiment, but why not dream of how high your own works can go? Why limit oneself?) I came to the conclusion that my own writing is Romantic, or at least, reaching for it. It depressed me to discover that I fit into a movement that took place two hundred years ago and has since dissolved. Yet it wasn’t just me thinking this way. Shortly after, I came upon essay after essay of writers talking about a new Romanticism. I don’t consider this a matter of memeing or copying one another, but a shared discovery of something… else.

There is some strange pattern in the world that we are all tapping into, something present in the digital airwaves. We can feel alone in the wilderness of ones and zeros, but we are alone together, connecting and merging into one another. We are forging a new nation, a digital, more complex nation. The Isle of Neoromanticism can be found in the soul.

Prelude

In 1977, NASA launched the two probes known as the Voyagers into space, each of which carried a 12-inch gold-plated phonograph record, a message from humanity. They contained nature sounds, music, and words meant to represent human life. There were many debates over what should be included. Carl Sagan said we must have music. The biologist Lewis Thomas suggested, “I would send the complete works of Johann Sebastian Bach … but that would be boasting.” They included it anyway.

Allemande

If we follow Hofstadter’s logic, it’s not Bach’s life that matters so much as the lives he has impacted, the lives that still follow his patterns.

Hofstadter analyzes Bach’s Cantata 197—Gott ist unsre Zuversicht (“God, Our One True Source of Faith”)—which is meant to accompany a wedding ceremony. He writes of the lyrics:

What struck me forcefully is that although they are being sung to a couple, they feature singular pronouns — du, dir, and dich in German and, in my English rendition, the obsolete pronouns “thou” and “thee”. On one level, these second-person singular pronouns sound strange and wrong, and yet, by addressing the couple in the singular, they convey a profound feeling of the imminent joining-together of two souls in a sacred union. To me, these poems suggest that the wedding ceremony in which they occur constitutes a “soul merger”, giving rise to a single unit having just one “higher-level soul”, like two drops of water coming together, touching, and then seamlessly fusing, showing that sometimes one plus one equals one.”

Courante

The patterns of an individual’s soul extend beyond themselves. And if you doubt this, Hofstadter says, just consider the act of speaking on the telephone. Physically you are in your backyard, stepping on the weeds, while simultaneously you are speaking with your doctor who lives five miles away, you’ve been in his office countless times, you can smell it just thinking about it, and he is thinking about you, maybe he can smell you too. The soul as a pattern can be less distinct the further away it is from its host, but still it exists, an implied harmony. Hofstadter wrote of looking at a photo of his deceased father: “For us, that photo is not just a physical object with mass, size, color, and so forth; it is a pattern imbued with fantastic triggering-power.”

It is a terrifying idea, that consciousness is just a pattern. This means it could be moved from one entity to another. A second body, the digital cloud, a Turing-complete computer of bananas. It is hard to imagine technology ever being able to reproduce what goes on inside us in all accuracy. By some estimates, there are 86 billion neurons forming 100 trillion connections to each other. If each connection was a star, the mind would contain 250 Milky Ways. We don’t have the capacity to reproduce this yet, and even if we did, I’m not sure if we could, but in the meantime there are crude approximations, most powerfully in the ones you love, but also, loosely, everywhere around you.

Sarabande

Have you ever wondered why the parts of each suite are called “movements”? With the ones named after dances, it makes sense—when you dance, you move. But the prelude is not a dance, and besides, this terminology applies to orchestral music as a whole, whether or not dance is involved.

The music moves you through time, from beginning to end. But also, it should reach in and grab you, move something inside you. Invoke your patterns. Music, Hofstadter says, is the closest one can get to understanding someone’s soul.

Gavotte I / II

Most readers can probably guess by now that I have been following the structure of the suites, and diligent ones are aware that I am on the fifth movement of the fifth suite, meaning there should be seven more movements after this one: two about the Romantic project, two about Bach’s history, two about the cello suites, and one about Hofstadter’s theory of consciousness. However I also gave myself the arbitrary limit of 5,000 words, which is already quite long, and which is swiftly approaching. There’s so much still to say, but I’ll have to leave the rest implied, after this next and final movement.

Gigue

I can usually spend forty-five minutes a day sawing on a string, letting my mind drift into the notes—but I don’t know why this is helpful, I can’t explain it. I’ve been practicing the second Bach cello suite for more than a year now, with only my two cats as audience, and they don’t care much for cello. Hofstadter says the small parts of life, the tiny neurons that push around the bigger symbols and patterns, aren’t worth thinking about. But playing the Bach cello suites makes me want to disagree. I feel as if I’m understanding the fundamentals of life, the way each note can add to something bigger. Yet each note itself contains a whole world unto itself. There is the bowing, the depth, the vibrato, the tone.

But the best moments are hard to force. They come when I’m outside, listening on my headphones as I watch evening light filter through the oak trees, as I watch fishermen stand still as statues on the dock, as I run so fast I can’t see anything at all. This is where the music opens up. I see the song split open, I feel the breath between each note. It’s like learning how to garden, when at first all you see is a great green mass, but eventually, you know every bud and seed. As the world grows more chaotic and unpredictable, ancient music becomes a stronger solace. I am in a composition that has played for hundreds of years and on it continues. Someone, somewhere is playing or listening to the suites right now. It could be you.

A beautiful essay. I read Godel Escher Bach as an undergraduate computer scientist about 35 years ago and have caried it in my head ever since. I was particularly struck by one section of your piece which inspired a short post of my own on the subject of poetry:

https://thisisnotapoem.substack.com/p/poetry-is-also-a-strange-loop?r=ouae5