Happy New Year?

A relatively recent and hotly contested innovation born of frustrated astronomers and bureaucrats, eventually enforced through papal fiat and global peer pressure

The wheel of the year is the rise and fall of a human life. The year is born on the vernal equinox as the first flowers bloom and the birds return. It grows and copulates and dances through the spring, celebrates its bounteous zenith at the summer solstice, becomes masterful and wise in autumn, then turns inward in preparation for its transition to winter. On the longest night of the year, the darkest of the dark, the year blows out its last candle and dies.

This pattern, the story of the Vegetation Deity rising and falling, is the ancient framework for the rites of the year. The drama of a human life unfolds in the annual cycle of the seasons. As the constellations twirl above us, so too the repeating myths of the year’s rituals tell the story of human life. In a sense, it’s a way to transcend the cruel joke of age: our wisdom increases as our strength decreases. By acknowledging and celebrating the passage of the seasons, we can grow wiser every autumn and be rejuvenated every spring. We rise and fall like the seasons; someday we will fall and not rise again, but someone else will, our children and grandchildren and the next generation, and so the big wheel keeps on turning.

Within this cycle, the spring equinox is the time of birth and new life. So why do we celebrate New Year’s in the dead of winter?

January is not a time for beginnings. It is not a time for initiative or turning over a new leaf. It’s not even an enjoyable time to have a party. Too dark, too cold. This is the time to hibernate, not change a damn thing, stay the course, survive, eat stew, snuggle, sleep.

But this particular calendar, a relatively recent imposition on human existence, seems to be here to stay.

Like nearly all ancient calendars, the first Roman calendar started on the spring equinox (approximately 21 March). The first four months of the Roman calendar were named after gods (Martius, Aprilis, Maius, Junius) and the next six were numbered (Quintilis, Sextilis, September, October, November, and December). This ten-month calendar, which Romans attributed to their legendary founder Romulus, comprised a year of 304 days.

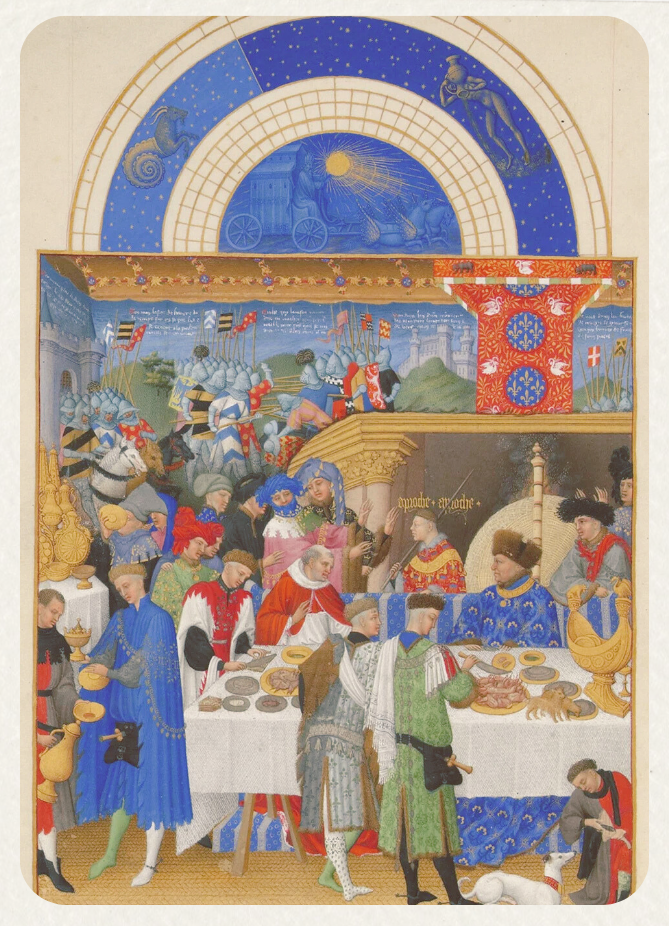

The 61-day gap in the dead of winter had no name. The days were not marked, and the world was dead; in fact, it belonged to the dead. The Romans are known for ancestor veneration, which was indeed an important part of their communal life, but there was a precautionary element to it as well. They lived in terror of the vengeful ghosts they deemed responsible for pestilence, death, ruined crops, and drought. These spirits had to be appeased, so the 61 unnamed days of winter were proffered as their time of dominion. During this calendric lacuna, Romans sacrificed goats and dogs, cleaned their houses with salt, and lit bonfires in the dark wintry streets. Especially penitent ones ran through the flames to purify themselves. Nude Luperci priests whipped spectators.

Roman king Numa Pompilius (715-673 BCE) apparently did not fear the wrath of the hungry ghosts and decided to end all this moribund nonsense. He added two more months to the calendar: Ianuarius (after Janus, god of beginnings) and Februarius (‘to cleanse by sacrifice,’ a small nod to the fearful rituals of the nameless winter days). His calendar had 355 days, and January was now its start.1

Absolutely everyone ignored this. They continued celebrating the New Year on the vernal equinox as they always had. For the next six hundred years.

In those six hundred years, however, Rome had expanded to span the Italian peninsula, the Mediterranean basin, and much of the Middle East. Running a republic and collecting taxes required a calendar with dates that recurred on an annual basis.

The lunar calendar of Numa Pompilius with its scanty 355 days fell out of sync with our actual 365-day solar year, resulting in all sorts of agricultural complications. Planting usually occurred around the vernal equinox, but the calendar had drifted away until the equinox fell in mid-May, which now had no relevance to the agricultural year. The calendar was an unreliable mess.

Julius Caesar decided to fix this. He invited the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes to put the calendar in a more sensible order. Sosigenes advised dropping the lunar system altogether and, for the first time ever, basing the year solely on the sun. This idea was met with howls from the Roman priests, who depended upon the lunar calendar for their rites.

But Caesar said it was to be so, so it was so. However, the calendar was at this point utterly out of rhythm with the solstices and equinoxes and in order for Sosigenes’ calendar to re-sync with the agricultural year, a hard reset was needed. The Long Year (or ‘The Year of Confusion’ as it became known), 46 BCE, lasted 455 days. The next year, 45 BCE started on 1 January.

Caesar did not get much time to enjoy the launch of his new calendar, as he was shortly thereafter stabbed to death. But his Julian calendar was adopted across the empire, replete with 365 days and 6 hours.

Alas for Caesar, Earth’s solar year is in fact 365 days, 5 hours, and 49 minutes. These eleven minutes added up over the centuries and slowly the sun danced away from the calendar yet again.

Despite the wide adoption of the Julian calendar, its preposterous 1 January New Year continued to be ignored. Everyone carried on celebrating the New Year at the vernal equinox as they always had, when days started to get longer, first sprouts peeked out from the soil, animals energetically copulated, and people began to waggle their eyebrows at one another.

This carried on through the Christianization of Europe, and, as church dates were selected to coincide with – and cover up – pagan holidays, the ecclesiastical calendar’s start date was set as mid-March, perched upon the vernal equinox, brazenly converting a joyful fertility and seed-planting festival into ‘The Feast of the Annunciation’ to solemnly commemorate Mary’s virginity and purity.

Exasperated administrators continued to advocate for the 1 January New Year, and the debate continued heartily through the Middle Ages until finally Pope Gregory XIII put the kibosh upon all calendrical opinions and in 1582 CE fixed the quirks of the Julian calendar via the invention of the leap year, proclaiming a definitive solar year that we still have to this day: the Gregorian calendar.

Italy, France, Portugal, and Spain were good sports (well, very Catholic) and immediately adopted the Pope’s calendar. Protestant and Orthodox nations dragged their feet. Great Britain and the American colonies continued celebrating New Year’s Day on 25 March for nearly two hundred more years, until 1752 when they finally acquiesced to the Gregorian calendar.

European colonization and the expansion of global trade networks led to the adoption of the Gregorian calendar in countries around the world. Many retain their older calendar systems alongside it; China, for example, started using the Gregorian calendar in 1912 but celebrates holidays and the New Year according to its own lunar calendar. In Myanmar, which uses an ancient Indian lunisolar system that dates back to 3012 BCE, is currently in the year 1387. In certain Southeast Asian countries, it is 2568 Buddhist Era, and in the Islamic world it is 1444 on the lunar Hijri calendar. But even in places that have maintained continuity with their ancient calendar systems, there is acknowledgement of the Gregorian system that now sets the clock of global commerce, finance, and technology.

In sum, the 1 January New Year is a relatively recent and hotly contested innovation born largely of frustrated astronomers and bureaucrats, eventually enforced through papal fiat, conquest, and global peer pressure.

A more successful calendar tale occurred in Persia. The marvelously accurate (more so than the Gregorian) Jalali calendar was calculated by the poet and polymath Omar Khayyam and adopted by the sultan of the Seljuk Empire in 1079. Its year starts sensibly on the vernal equinox: Nowruz, meaning ‘new day,’ continues to be celebrated around the world with dancing, gifts, poetry recitations, visiting family, feasting, spring cleaning, and haircuts. Children decorate colorful eggs and leap over small bonfires. A table is laid with traditional foods symbolizing rebirth, sunrise, fertility. A proper new year.

Meanwhile our 1 January New Year’s Resolutions are made with the dim horror of someone haunted. I must stop eating so many sweets. I must get back to the gym. I must call my estranged sister. Before these tiny hopeful specks can get a drop of sunlight to give them life, the dreadful month of February descends upon them, devouring all hope of change. Oh well. There’s always next year. And so it repeats.

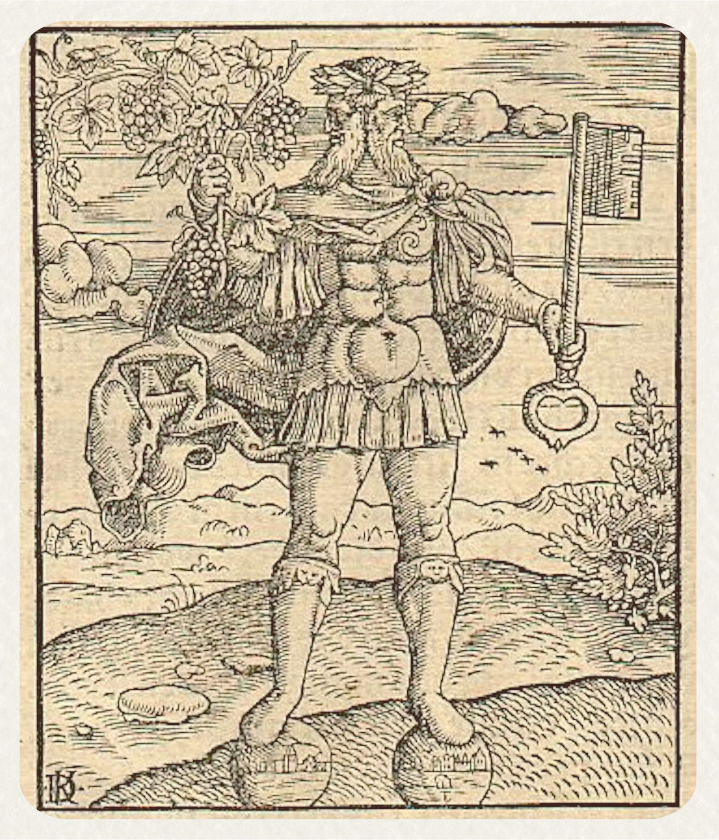

The only small concession I’ll make to this day: I rather like Janus the Roman god of portals, transitions, and beginnings. His double-faced image was often put over doorways— one face looking inward and one outward, one eye to the past and one to the future. As you enter this world, so shall you exit. In this sense, I begrudgingly accept January as the gateway to the year.

So friends, Happy New Year I guess.

A different source says Numa tacked Jan/Feb onto the end of the calendar, keeping the March start-date and that it was a Roman bureaucrat several hundreds of years later that first insisted on 1 January. So, unknown who/when exactly it was, but the March vs. January New Year debate was real, vehement, and ongoing for at least eighteen centuries.

Next Tuesday: Join us as the Epiphanies Reading Series returns to New York for the Feast of the Epiphany on Jan. 6, 2026 at a very special place: St. John’s Church in Greenpoint (stjohnsgreenpoint.com).

The theme is the Gift. Readers will include Samara and other surprise guests.

Pay what you want for our donation only tickets—but please help us!—available through the Eventbrite link:

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/epiphanies-the-gift-tickets-1979485356989?utm-campaign=social&utm-content=attendeeshare&utm-medium=discovery&utm-term=listing&utm-source=cp&aff=ebdsshcopyurl

My understanding is that January first was the date when the Roman consuls entered office. It's an odd date for the year to start. I'm all for switching it back to the Vernal equinox or Annunciation.