Notes on The South

Bring up your dead

1. The sound of the South is the distant whine of leaf blowers on a blue afternoon.

2. In the Laws, Plato wrote: “with regard to places, we mustn’t fall into the error of thinking that there are not those which are more suited to making men better and less good.”

He’s saying that it is not all subjective and preference, there are literally good places and places that are literally less good in the world.

Places that have, as he puts it, “divine breath” and places that are the “haunts of demons.”

I’d say the South is somewhere in-between, possessing both of these things.

3. There is a Southern frequency that must be settled into like silt, or those half-pigeon positions in yoga. Any attempt to glide along with a harried, meritocratic time-sense imported from the North or any other ganglion of 24/7 capitalism will be met with dissonance. If you pay attention, you will come to realize that the South is fundamentally anti-modern, agrarian, populist.

4. The South can only live in extremes. There is no possibility of a middle way. Good enough. Never has been. Everything has to be either/or. America is an either/or country. You’re not allowed to be neither/nor.

The South might be the most either/or place in America.

5. The South was, in its broadest contours, 19th century Russia. Memoir of underdevelopment. A peasant, agrarian slave/serf society topped with a frosting of pampered intellectuals and farmer-aristocrats, with economic and social lives split between country estates and a few major cities where trading and socializing was done. Their leisure and capital was built on human and agrarian exploitation. Both countries “abolished” slavery around the same time and immediately set up replacement systems of indentured servitude.

There is a hidden bond between Southerners and Russians, a vastness, a deep attachment to the land and to childhood, a tiredness about being yelled at and misunderstood, an overdone and extreme sense of largesse and politeness, and a love of nature and land that is vast and full of mystery.

6. I don’t see how you can look at what Huey Long did in Louisiana—the insane Louisiana State Legislature skyscraper straight out of 1930s Moscow—and not see Stalin on the bayou.

A centralizer and modernizer who meant to bring his people into the 20th century by any means necessary.

7. The South was basically war-torn and cut off from the rest of the country for a century. That is, until the construction of I-95. which started in 1956 and was completed in the 1970s. That meant nearly a hundred years of inaccessibility and post-war decay.

Visiting Savannah after World War II, Lady Astor called it “a beautiful woman with a dirty face.”

Before I-95, you could buy and move into the crumbling, center-city antebellum homes in Charleston and Savannah for next to nothing. But no one wanted them. This is the story of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil—Savannah real estate.

8. There are really only two kinds of cities in the South: one has a tight walkable downtown and is reliably liberal or even sort-of leftist and is the kind of place a DC-area non-binary person would want to live and you don’t really need a car to live there (though it always helps). Savannah, New Orleans, Chapel Hill, Gainesville, Charleston to some extent.

The other has culture and food and parks and stuff but it’s all hidden within an endless web of suburbs and sprawl and local beltways—yes, you can usually find a good bookstore or magick shop or hot yoga easily, but it will be a 15-30 minute drive out to some strip mall. Houston, Raleigh, Atlanta, Jacksonville.

9. 2010-25 has been a rapid and unprecedented period of migration to The South, peaking in 2022 with work-from-home. As a kind of internal exotic colony, it has been rediscovered and re-populated by people from the rest of America and other parts of the world.

There have always been transplants to the South, and this is good, but this process accelerated to a ridiculous degree during the pandemic. Young and old who were unsatisfied in their climates and cities moved to the South en masse and bought houses—and from what I’ve seen, a lot of them also bought big new gas-guzzling trucks so they would fit in better.

They liked the South for its pace of life and weather and culture, but they also were destroying the things they like about it—they are the harbingers of standardization and the monoculture.

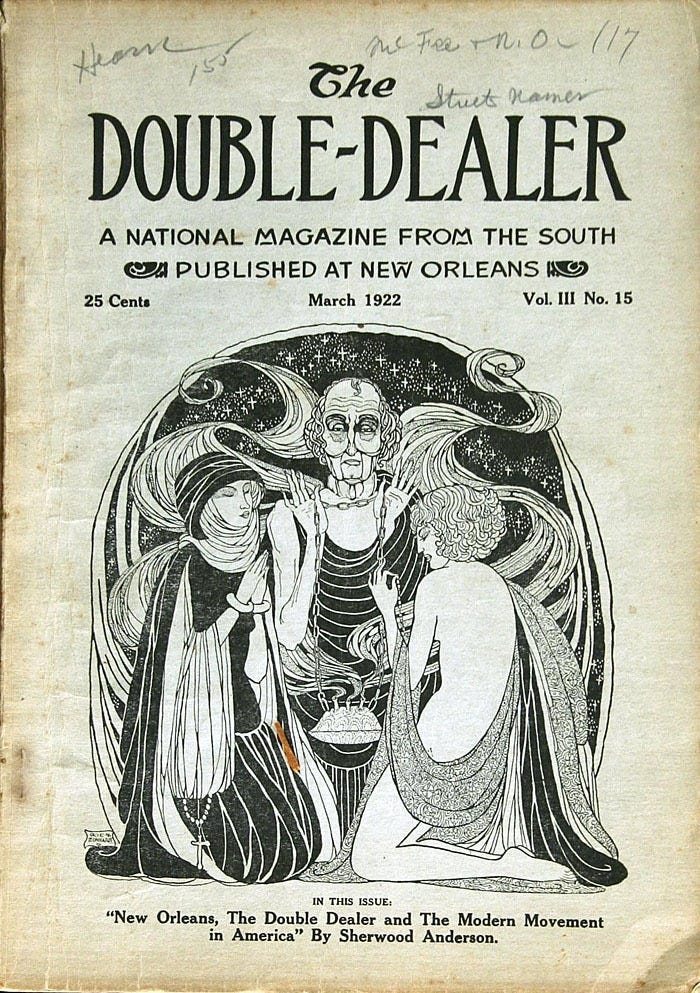

10. The South has at various times attempted to build an indigenous, autonomous literary culture. The Double Dealer in New Orleans published the major modernists: Djuna Barnes, Joyce, Sherwood Anderson, Faulkner, etc. Of course more recently you have had Oxford American, Sewanee, The South Carolina Review, The Georgia Review, periodic rumblings out of New Orleans of new start-ups, you have the people around Duke University who started Scalawag.

But most modern-day efforts flicker away into one of two categories:

Highly-acculturated academic-affiliated transplants who come live for a while down in the exotic colony, importing a kind of ideology and literary culture from other places in a way that arouses hostility and suspicion. Or rather it just becomes a colony.

Older natives who are so occupied with the past and the worship of deceased local lit gods (Barry Hannah, O’Connor, Conroy, Percy) in a way that squeezes the air and life and sense of possibility out of the endeavor—basically it becomes a senior citizen book circle. New life and new growth cannot take root in such conditions.

11. The South filled him with a kind of loathing and malaise when he was there. A kind of inconsolable rage grew in him against the lands’ silent shrugging judgment, which seemed to say, like the goodbye of an icy lover, you gave me up and it’s your loss. Seeing it again always increased the pain of the path not taken. But when he was in the rocky-eyed Northeast, he always presented himself as “A Southern Man”, proclaimer of the South, defending it against slights as a dignified place, as a true place. He smashed down on all Northerners when they used fake Southern accents, when they talked about backwater hillbillies holding the country back. It offended him, like a friend making an off-color and all-too-true observation about a family member.

Although it was clear to all involved, most of all himself, that he defended from a place of shame and agony over something he was not, because if he was, he would be there, he would have never left there; if he was, he would have a real accent, but he was not and did not anymore—and everyone could tell that he lived in the city because he wouldn’t fit in down there and by portraying himself as something was trying to identify himself as something special, but he was just another person from some place else. The truth infuriated him. He could neither picture himself staying and dying in the city like the elderly people with walkers in his building that took hours to climb to their sweltering fourth-floor apartments, nor could he imagine himself actually going home, getting a house, mowing the grass, having a family, pumping the air-conditioning, grilling.

12. My grandfather on my mom’s side was a part of a diaspora of Lebanese immigrants who fanned out from New Orleans across Louisiana and Mississippi in the 1920s and 30s. My grandmother, a Cockney from London, emigrated to be with my grandfather, but never quite took to the region. She called it “this godforsaken place you’ve brought me to.” She never became an American citizen. But after my grandpa died, she didn’t go back to England either.

My father’s side were hardscrabble, self-sufficient Appalachian yeoman people from the foothills of North Carolina—canning their own beans, growing their own stuff, not going to church. They were straight out of the Foxfire book or people James Agee met in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. When I was a young punk rocker who patched up all his clothes with crust bands, my grandpa jokingly started calling me “Patches.” But he had patches on all his overalls and clothes too.

The Smiths had been just getting by in Wilkes County for hundreds of years. According to my grandfather, his great-great-grandfather lived in a cave to avoid having to fight in the Civil War. Either he was a coward or hated war or simply thought: I have no horse in this race.

No slaves so what do I care, not my war.

13. When I was in elementary school, I had a heavy South Carolina accent. When we moved to the Triangle region of North Carolina, I was put into a very good and very diverse public school where I was exposed to different kinds of people from all backgrounds and all over the world. I am very grateful for this, it is the only reason I am who I am today.

But also, I was put into speech therapy, where I was taught how to speak proper, i.e., lose the Southern accent, so I would have “more opportunities in life.”

I deeply resent it.

14. I often wish I just stuck around the South long enough to become the Salt-Life normie I was born to be and marry up with a nice, well-adjusted UNC/Duke girl, maybe a nurse or a dentist. We’d have one house in Ocracake and one in Highlands or Lure and go between the mountains and beach getting tanned and ruddy and smiling—instead I took my damnable road to oblivion through the swamp of Anarchyland and from there a decade in hungry-ghost Brooklyn, before disappearing into the fog of Sweden.

15. The coffin was heavy and shiny, his face was waxy and cold and made-up in the open casket. It was hard for me to accept that that face was him. The police stopped traffic through the town and the hearse made its way up to the desolate hill-top cemetery.

16. On a recent trip home, I found myself increasingly drawn towards the places that, beyond the boundaries of the jaw-dropping Covid migration, the highly-educated Northeastern corridor people are still afraid of—too backwatery, too “cultureless,” too off-the-map for their interests.

In these places, I saw traffic thin out and grocery prices drop and things were calm and good and were The South I remembered from the first 20 or 30 years of life.

These places, surprisingly, also turned out to be the most interesting culturally, the most racially-integrated, with the best random affordable places to eat, the best bars, the best overall in every way honestly.

I almost wanted to say to them, Yes yes, keep it, keep your bad “undesirable” reputation that you’re horrible, racist, underdeveloped places that no one would ever want to live or visit, and in that way you won’t be turned into yet another overpriced standardized playground.

17. This summer, I was sitting on the patio at the redneck bar on the inlet, draped with gorgeous Spanish moss and Disney-like animals frolicking in the grass. A cover band was playing The Hollies and the Boomers were all dancing and doing the shag, and a woman in her fifties from Pennsylvania started talking to me.

She said she had just moved down to the area two weeks before. “I bought my house down here sight unseen, but when I got in there’s frogs and spiders in it! A brand new house. Can you believe it?”

“And it’s such a far drive to everything! I came down for the weather but there’s just no Culture down here, where’s the Culture. We could walk and there were cafes in State College! But the weather was so bad...”

I could see the NPR-ness popping out of her eyeballs. I nodded along telling her it would get better, offering recommendations. And if she didn’t like it she could sell the house.

But I also wanted to say: Look around you, look at the moss and sand, at the fireworks stores and vape shops and Jurassic mini-golf places and strip clubs, this IS a culture, is it really much worse than your Northern “culture”? Just nicer people and better weather but the same shit everywhere, but of course I instead just said: it would get better, and she could always sell the house and move if it didn’t work.

The list of annoying things about life in the South is long: walkability, pisspoor infrastructure, potholes, a haphazard approach to zoning and planning of any type, architecture of the eyeballin’-it school of architecture, water supply that often has PFOAs or other industrial excrete, food deserts, bad healthcare, you name it.

But while the Northern white ladies complain, the Latinos and Indians sure seem to love it—plenty of work, big trucks, loose regulations around small business formation, good weather, big yards for the big families to play in, live and let live, sunshine, beautiful parks and beaches. The good life.

Or maybe I’m just Young Werther-ing out, romanticizing a way of life I could never actually stand to live.

—Aaron Lake Smith

This is beautifully observed and beautifully formed. The only way to write about the South is aphoristically. For a non-Southerner, the South is a moral spitoon--to appropriate a phrase from Faulkner--into which they can expell the collective sins of America. The South is an idea that clears their conscience; but the South in the Southern mind is no monolith: it's analogous to the ancient Greek city states--a shared heritage among fiercely local identities. What does Lafayette have to do with Roanoke or Tallahassee with Little Rock? I once saw a bar fight between two guys over which was better, Allen Parish or Beauregard Parish. I grew up in the adjacent Calcasieu Parish, and I couldn't tell you the difference between Allen and Beauregard, but they could. What I can tell you is that they are both idiots: Calcasieu is by far the best.

As a lifelong, though well-traveled, Southerner, this all hits so true. Especially this perfectly summated line, which I still thinks informs a lot of the culture today, "Their leisure and capital was built on human and agrarian exploitation. Both countries “abolished” slavery around the same time and immediately set up replacement systems of indentured servitude."