Elegy and Effigy

Arresting Time’s Flow in Freud, Sacks, Bazin, Ariès, Munro

Cop: You own a video camera? Fred: No. Renee: Fred hates them. Fred: I like to remember things my own way. —David Lynch, Lost Highway Words alone are certain good. —W. B. Yeats, “Song of the Happy Shepherd

If it were up to me, photography would not exist. If it were up to me, I would never be photographed, and all images of myself and of everyone else would be spontaneously destroyed. (Yes, yes, of course I also love photography and film; but that is because I am willing to acknowledge and accept a fundamental amorality—even, perhaps a fundamental evil—in art, as it feasts upon and transmutes life into itself. But I am not obliged to submit myself or those I love to that same discipline.)

What fantasy does photography cater to? It’s as if we had convinced ourselves that time will afford us a vantage point from which to summon everything we once lived into presence—but is this not what we must learn to give up?

A freeze-frame, meanwhile, is nothing but repetition of the same.

So I wrote some while ago, and so I still largely think—torn between contrary impulses. That ambivalence came back to me recently reading my fellow editor

’s superb recent essay “Don’t Look Now: On Loss, Losing, and Repetition.” In this moving blend of personal and critical reflections, weaving together Freud, Elizabeth Bishop, and a superb reading of Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973), Galluzzo produces a secular account of the Fall in each of us and in himself, of which the locus classicus is the fort-da game staged by Freud’s grandson, as described in Beyond the Pleasure Principle. As Galluzzo writes:This is quixotic mastery: the child re-stages both mother’s departure—now fantastically reconstituted as subject to his own will—and, more importantly, her reappearance. But, as Freud notes: “It may perhaps be said in reply that her departure had to be enacted as a necessary preliminary to her joyful return, and that it was in the latter that lay the true purpose of the game. But against this must be counted the observed fact that the first act, that of departure, was staged as a game in itself and far more frequently.”

In seeking to master loss through repetitive recreations, we work to further such loss. We serve Thanatos in striving to beat it better this time around. Tragic irony is the determinative principle of psychic life.

***

In Freud’s story, this is the traumatic first act of individuation: an infantile and secular version of the Fall for each of us, but even more so for good little boys with obsessive-compulsive tendencies.

Reading Galluzzo’s account of an endless, almost willed propensity to lose—one that is ambiguously poised between openness to time’s flow and its opposite, the effort, by repetition, at freezing time into non-existence—that is, of his account of an art of losing that seems to have two modes of expression (call them, after T. S. Eliot, two “conditions which often look alike / Yet differ completely, flourish in the same hedgerow”), I could not help being put in mind of an ambivalence of my own—an ambivalence apparently far less intimately situated, yet in its own way just as deep. I thought of my own ambivalence, that is, with regard to photographic images—whose best interpreters understand their pathos in relation to our experience in the flow of time. What to make of these sometimes living, sometimes chilled amputations?

At the risk of a certain a-romantic formalism—a-romantic because the Romantic spirit will never finally accept any deterministic account of artistic form, any more than it will accept as decisive any other imposition of an unenlivened object world—I here consider the affordances of two arts: poetry and photography.

In his epochal The English Elegy: Studies in the Genre from Spenser to Yeats (1981), poet and scholar (and now painter) Peter Sacks connects the literary form of the elegy—its characteristic invocations of the dead, its repetitions, its pastoral images of nature ravaged and denuded in sympathy with the mourner—to what my fellow editor Anthony Galluzzo has described, quoting Freud, as “the child’s great cultural achievement: the instinctual renunciation (that is, the renunciation of instinctual satisfaction) which he had made in allowing his mother to go away without protesting.” The means by which the child has “compensated himself,” as Freud puts it, is the fort-da game: a re-enactment of its mother’s departure and return, yet symbolized by objects within reach, within the child’s control.

For Sacks, this “cultural achievement” finds its echo in classic elegiac tropes: the lost (or escaped) beloved who turns into a laurel (Daphne) or reed (Syrinx), respective emblem and instrument of poetry. “The movement from loss to consolation thus requires a deflection of desire, with the creation of a trope both for the lost object and for the original character of the desire itself.” The tropes of poetry re-enact the tropes of the soul—those gestures by which a principle of self-limit (repression, renunciation) converts loss into difficult gain: “At the core of each procedure is the renunciatory experience of loss and the acceptance, not just of a substitute, but of the very means and practice of substitution.”

If death is the mother of beauty, mourning is the mother of metaphor. Substitution is the core of all art. No wonder statues are marble: the metaphoric is metamorphic, renunciation and repression are as the geologic pressures converting limestone—that compaction of pulverized shells—into something lucent and teasingly like flesh.

For Sacks is not the only one to link art-making and funerary practices, nor are such reflections only an affair for poets. The French film-critic André Bazin’s essay on “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” published posthumously in 1959, remains one of the most suggestive reflections on that medium. Today, when our sense of the indexical, of the impress of reality upon the photographic plate seems on the verge of passing into digital obsolescence, it is all the more incumbent upon us to grasp it.

Bazin’s opening gambit links art-making and the dead: “If the plastic arts were put under psychoanalysis, the practice of embalming the dead might turn out to be a fundamental factor in their creation. The process might reveal that at the origin of painting and sculpture there lies a mummy complex.” As he explains, “The religion of ancient Egypt, aimed against death, saw survival as depending on the continued existence of the corporeal body. . . . To preserve, artificially, his bodily appearance is to snatch it from the flow of time, to stow it away neatly, so to speak, in the hold of life. . . . The first Egyptian statue, then, was a mummy, tanned and petrified in sodium.”

But Bazin has his own story to tell about the need to come to terms with signification—what, for Bazin, is not just “the child’s great cultural achievement” but the great cultural achievement of the childhood of visual culture. This he ascribes, wittily, to entirely practical considerations:

But pyramids and labyrinthine corridors offered no certain guarantee against ultimate pillage. Other forms of insurance were therefore sought. So, near the sarcophagus, alongside the corn that was to feed the dead, the Egyptians placed terra cotta statuettes, as substitute-mummies which might replace the bodies if these were destroyed. It is this religious use, then, that lays bare the primordial function of statuary, namely, the preservation of life by a representation of life.

So, mummification is inconvenient. (Though what is inconvenience but a stand-in for all of the imperfections of our living in time?) Hence the shift from preservation to representation: from the mummy—vain effort at preserving the thing itself—to the statue, symbolic substitute. Like the laurel and reed in Ovid as interpreted by Sacks, not only does it stand in for the lost object, the body of the dead, but is a means of training us to reattach our affections from the real to its representation. This is never fully satisfying. The statue is, in the most literal sense, cold comfort. Or so Admetus, the mourning, guilty husband discovers in Euripides’ play, embracing his lost wife Alcestis, in effigy, in his bed.

Hence that strain of art—call it Romantic or Tragicomic—running from Euripides’ Alcestis itself up through The Winter’s Tale and the Munk-Dreyer Ordet, that raises such yearning to a higher power by ending with a miraculous restoration of the dead: in the flesh. (Not coincidentally, such stories tend to center on forgiveness; for forgiveness implies the acceptance, by the one granting it, of the wrongdoer’s mortal limitation, which it thereby raises to a higher power. And so even such tales of miraculous return teach us to accept the limit of death.)

Yet there is a twist in Bazin’s account: the return of the repressed. For Bazin’s telling of the novelty of photography—of its “essentially objective character,” of how “All the arts are based on the presence of man, only photography derives an advantage from his absence,” of how photographic images affect us “like a phenomenon in nature, like a flower or a snowflake whose vegetable or earthy origins are an inseparable part of their beauty”—also reveals this most modern artform as a throwback to art’s most primitive impulses. The photograph, which Bazin will insist again and again not only bears the literal impress of the object, but “is” the object, which it thus wrenches out of time, marks the recrudescence of the mummy complex.

On this point, Bazin could hardly be more emphatic. Here he describes how painting—for centuries half in love with what photography has now revealed as the false, because mechanical, god of verisimilitude1—has been liberated by obsolescence:

Besides, painting is … an inferior way of making likenesses, an ersatz of the processes of reproduction. Only a photographic lens can give us the kind of image of the object that is capable of satisfying the deep need man has to substitute for it something more than a mere approximation, a kind of decal or transfer. The photographic image is the object itself …. No matter how fuzzy, distorted, or discolored, no matter how lacking, in documentary value the image may be, it shares, by virtue of the very process of its becoming, the being of the model of which it is the reproduction; it is the model.

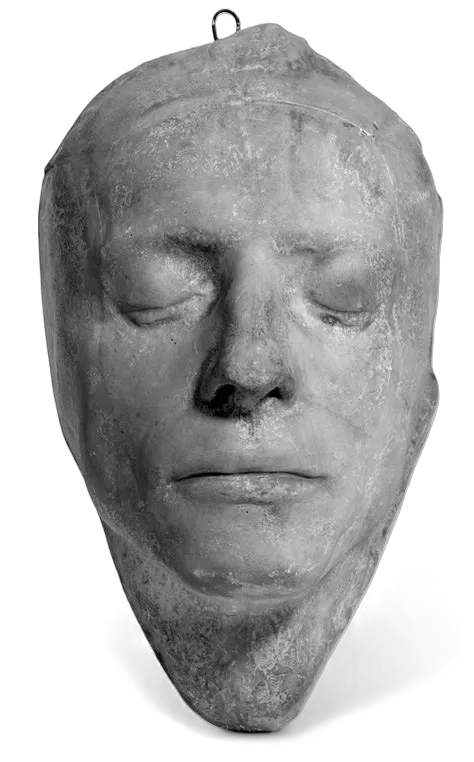

Hence those arresting phrases with which Bazin characterizes his own most cherished artform, that of motion pictures: “photography does not create eternity, as art does, it embalms time” and that “Now, for the first time, the image of things is likewise the image of their duration, change mummified as it were.” Hence, too, that curious footnote in which he acknowledges another precedent for photography in its automatism, identity with its object, and funereal intent: in “the lesser plastic arts, the molding of death masks, for example, which likewise involves a certain automatic process. One might consider photography, in this sense as a molding, the taking of an impression, by the manipulation of light.” (Another footnote will observe “that the Holy Shroud of Turin combines the features alike of relic and photograph.”)

Suppose we are to take this essay’s argument seriously, that is, literally? What, in particular, to make of Bazin’s claim that the photograph is the object (in the way a mummy is the dead). What does it mean for mourning—normatively, since Freud, a process, however painful, of the reattachment of libido rather than the perpetual cherishing of a lost object (or, as in melancholia, the nursing of an inarticulable loss)—if we have regressed from the acceptance of symbolic substitutes into cherishing a death mask or a photographic “embalming” that teases us with the thought that it is the lost object?

But suppose ours is only one historically specific—and perhaps uniquely diseased—response to the fact of death. So argues Philippe Ariès, the great French scholar of the Middle Ages and private life, in his study of Western Attitudes Toward Death. For if we have regressed in the manner Bazin suggests, then Ariès tells how.

On the present-day experience of death—most immediately, that of the auditors to whom he delivered it as lectures at Johns Hopkins, in Baltimore—Ariès is unsparing. Ours is a society of compulsory happiness, in which there is “the moral duty and the social obligation to contribute to the collective happiness by avoiding any cause for sadness or boredom, by appearing to be always happy, even if in the depths of despair.” In such a society, pain and loss have no place:

The American way of death is the synthesis of two tendencies: one traditional, the other euphoric. Thus during the wakes or farewell ‘visitations’ which have been preserved, the visitors come without shame or repugnance. This is because in reality they are not visiting a dead person, as they traditionally have, but an almost-living one who, thanks to embalming, is still present, as if he were awaiting you to greet you or to take you off on a walk. The definitive nature of the rupture has been blurred. Sadness and mourning have been banished from this calming reunion.

One influence on this US practice (which includes embalming) is commerce: “In order to sell death, it had to be made friendly.” And the same need to draw a veil governs the contemporary experience of death itself. The modern world, Ariès observes, demands an “acceptable” death—a telling thought in our euthanasic age, yet one the Romantic reader ought too easily to follow Ariès in dismissing, lest one trivialize the wish “to cease upon the midnight with no pain.”

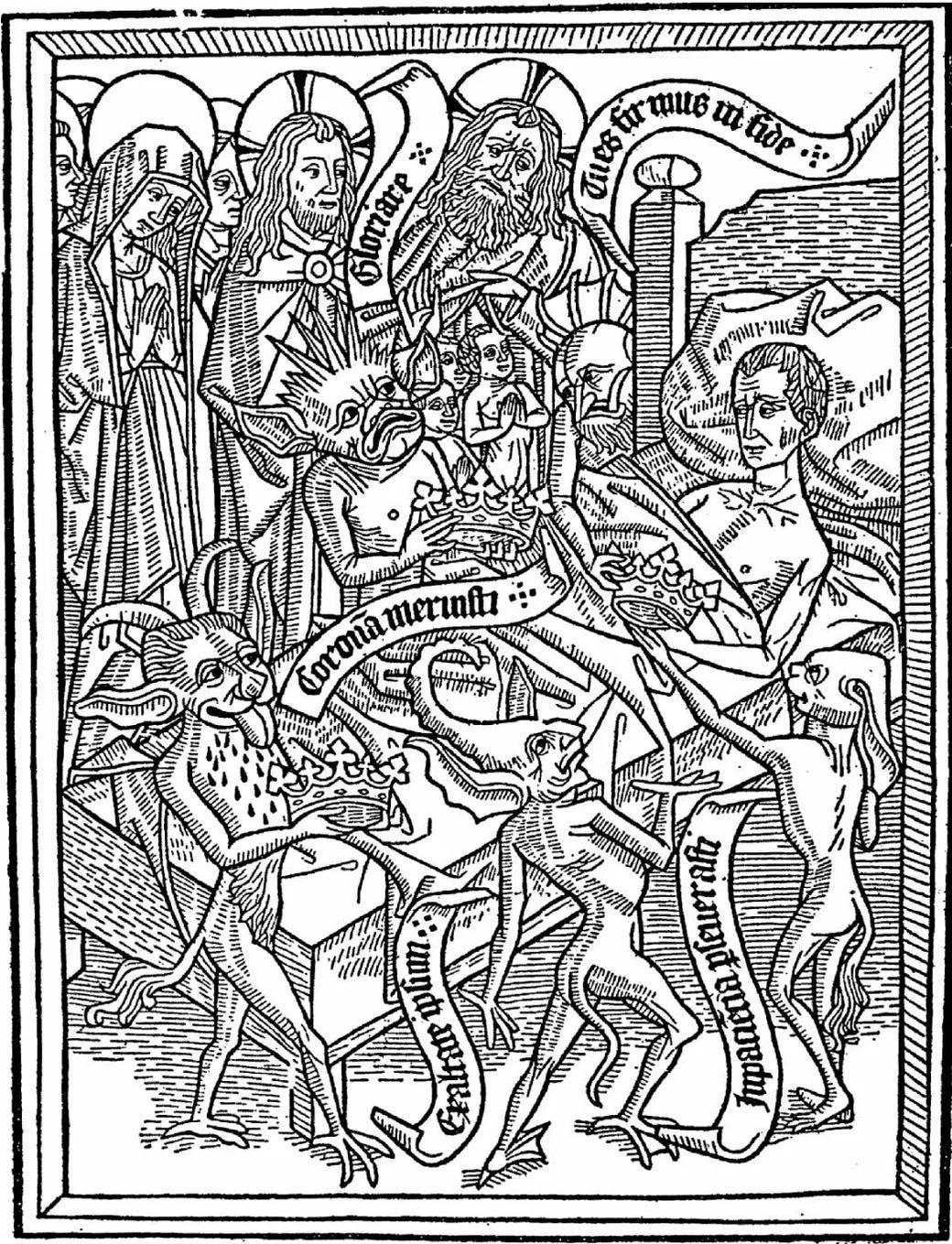

Far from the dramatic deathbed spectacles of medieval manuscript illustrations, where the mortally ill man or woman, surrounded by loved-ones, faces their Last Temptation, modern-day death “must remain discreet and must avoid emotion”:

In our day, in approximately a third of a century, we have witnessed a brutal revolution in traditional ideas and feelings, a revolution so brutal that social observers have not failed to be struck by it. It is really an absolutely unheard-of phenomenon. Death, so omnipresent in the past that it was familiar, would be effaced, would disappear. It would become shameful and forbidden.

Our day’s “brutal revolution,” as Ariès calls it, is in part the offshoot of an earlier revolution of the thirteenth century. For there are, from the perspective of the historian of death, not one, but two Middle Ages; we are living in the aftermath of the second. This Ariès reveals in the relative prominence of two kinds of art: the frieze of the Last Judgment (the characteristic visual emblem of the earlier Middle Ages) and the portrait (already mentioned) of the individual on his deathbed from later manuscript illustration. To these two forms of art corresponds a theological difference. In the emphasis on the Last Judgment, resurrection is a collective affair.

In place of “the familiar resignation to the collective destiny of the species [that] can be summarized by the phrase, Et moriemur,” a new attitude now prevails: “Since the Early Middle Ages Western man has come to see himself in his own death: he has discovered la mort de soi, one’s own death.”

With this discovery of one’s own death, an aspect of modern individualism, was unleashed an entire repertoire of visual representation, up to and including the tradition of the effigy. Although, in the thirteenth century the effigy “evoked the beatified or elected person awaiting Paradise,” with time it became “increasingly realistic and attempted to reproduce the features of the dying person. Finally, in the fourteenth century, realism was carried to the point of reproducing a death mask.” And so was born that “lesser plastic art” that, for Bazin, marked the spiritual (and practical) origin of the photograph.

Modern man is notionally free to carve his own path in life, without constraint. As such, however, he is afflicted by a new burden:

Today, the adult experiences sooner or later--and increasingly it is sooner--the feeling that he has failed, that his adult life has failed to achieve any of the promise of his adolescence. This feeling is at the basis of the climate of depression which is spreading through the leisured classes of industrialized societies.

“This feeling,” Ariès notes, “was completely foreign to the mentalities of traditional societies. “On the contrary the man of the late Middle Ages was very acutely conscious that he had merely been granted a stay of execution, that this delay would be a brief one, and that death was always present within him, shattering his ambitions and poisoning his pleasures. And that man felt a love of life which we today can scarcely understand, perhaps because of our increased longevity.”

Such a feeling—of having wasted one’s life, one’s promise—is indeed a rite of passage in modern societies. It is also a key theme in Romantic poetry, showing the wish to be still strong among those who have genuine love of life and freedom, not only among those who, as Ariès suggests, experience a merely given pseudo-freedom as a source of enervation rather than vitality. “—Was it for this,” Wordsworth asks in The Prelude “That one, the fairest of all Rivers, lov’d / To blend his murmurs with my Nurse’s song, / And from his alder shades and rocky falls, / And from his fords and shallows, sent a voice / That flow’d along my dreams?” And we find a similar impulse in such neoromantic works as Pier Paolo Pasolini’s graveyard poem “The Ashes of Gramsci,” an Italian echo of Shelley’s “The Triumph of Life” set in the Cimeterio Acattolico in Rome, where Shelley and Keats, too, lie buried—and where defeat of the poet’s political hopes (a belated Communism) is linked to the fate of his youth. Accordingly, the poet recalls lines of Wordsworth (“And O ye Fountains. . . ”) and hearkens to the City’s erotic promise. At stake in all these poems would seem to be the quality of our dissatisfactions—whether they impel us to fresh life or to mere stagnation, including the stagnation of frenetic activity. (Recall again the freeze-frame. Repetition is the projector’s only sostenuto.)

And it is also the theme—wasted life, wasted promise—of the next work I will consider, which returns us to the problem of life and time’s flow and the deathliness of the photograph.

Alice Munro’s “Lichen,” from her 1986 collection The Progress of Love, tells the relatively simple story of a visit paid by David, a city-bred civil servant, to his ex-wife Stella in her rural farmhouse. (At least one critic, noted its rural setting and quotations of renaissance madrigals, has dubbed it a “pastoral.”2) The occasion is the birthday of Stella’s father and David’s ex-father-in-law, a figure of steely wheelchair-bound manhood, eunuched by age but still somehow David’s superior, to whom David continues to offer tribute. David is joined on his visit (to Stella’s house but not the care home) by his new girlfriend, the willowy tranquilized hippie Catherine.

The progress of the story shows David and Catherine enduring the jovial but inevitably mildly oppressive hospitality of Stella, an amateur historian and writer who has, to David’s consternation, let herself go, resigned herself to nature and to time. “There’s the sort of woman who has to come bursting out of the female envelope at this age, flaunting fat or an indecent scrawniness,” David reflects, as he pulls into the drive, and Stella is one of them. But David himself is a type. David has shown up not alone, and we soon learn he is not alone in more ways than one. This David reveals to Stella in scene when, leaning against her kitchen counter, watching her peel apples, “He reaches quickly into his inside pocket, and before Stella can turn her head away he is holding a Polaroid snapshot in front of her eyes.” (The reader has already seen him flash the Polaroid, without seeing its contents, to the husband of a pair of jogging retirees he and Stella met while picking up whiskey in town before visiting her father.)

“That’s my new girl,” he says.

“It looks like lichen,” says Stella, her paring knife halting.

“Except it’s rather dark. It looks to me like moss on a rock.”

“Don’t be dumb, Stella, don’t be cute. You can see her. See her legs?”

Stella puts the paring knife down and squints obediently. There is a flattened-out breast far away on the horizon. And the legs spreading into the foreground. The legs are spread wide—smooth, golden, monumental: fallen columns. Between them is the dark blot she called moss, or lichen. But it’s really more like the dark pelt of an animal, with the head and tail and feet chopped off. Dark silky pelt of some unlucky rodent.

We should not be misled, either by the mores of our moment, now recovering from its latest rashes of moralism, or by the vehemence of Munro’s language, into assuming this story is meant as simple condemnation of David.3 David is us—in a way that Ariès and Bazin help us recognize, and that I think Munro does too. And so, when the end of the story presents a contrary perspective—that of Stella—we likewise encounter not what we statically are, but a vantage-point (on loss, on eros, on art) that we (or Munro) might achieve (though at the price of an acquiescence in marginality and decay that we might be unwilling to make; so unsentimental is Munro’s vision).

David is Ariès’s modern man; accordingly, he is also Bazin’s, and Freud’s. His endless shuttling through objects of libidinal attachment—ever new objects of desire—suggests, not so much an enlivening eros, as an unwillingness to detach the libido from its primary object: himself. (Freud, significantly, finds within melancholia, mourning’s double, a strong element of masochistic narcissism.) David seeks to evade death: by dyeing his hair, by chasing and fucking ever younger women, by cherishing a photograph of one woman that “embalms” her and his desire in a single image by which, fort-da-like, he can manage and forestall vitality’s departure. Of melancholia, another chief symptom, for Freud, was exhibitionism: this is visible in David’s mixture of boasting and self-degrading (by exhibiting his compulsions). Thanatos rears its head in such performances, as in the mechanized images he associates with the “bad girl” Dina, whom he remembers gleefully winding up toys (much as she winds him up) and sending them down the hallway to crash. David’s crotch shots are another mechanical effort at control, teetering on the brink of its opposite. The photograph here quite literally is its object, is what Dina is to David: embalmed cunt. Death and life enfolded, frozen at the source.

And yet—in the story’s final moments, a transformation. In a typical Munro epilogue, we find ourselves alone with Stella at home, “a week or so” after David and Catherine’s departure. I quote the passage in full:

A week or so later, when she is tidying up the living room, getting ready for a meeting of the historical society that is to take place at her house [we have previously learned that Stella is a contributor to the historical society’s circular, and thus, in that minimal sense, a writer—as she self-deprecatingly, but also significantly, puts it: “quite the budding authoress], Stella finds the picture, a Polaroid snapshot. David has left it with her after all—hiding it, but not hiding it very well, behind the curtains at one end of the long living-room window, at the spot where you stand to get a view of the lighthouse.

Lying in the sun has faded it, of course. Stella stands looking at it, with a dust cloth in her hand. The day is perfect. The windows are open, her house is pleasantly in order, and a good fish soup is simmering on the stove. She sees that the black pelt in the picture has changed to gray. (It’s bluish or greenish gray now. She remembers what she said when she first saw it. She said it was lichen. No, she said it looked like lichen. But she knew what it was at once. It seems to her now that she knew what it was even when David put his hand to his pocket. She felt the old cavity opening up in her. But she held on. She said, “Lichen.” And now, look, her words have come true. The outline of the breast has disappeard. You would never know that the legs were legs. The black has turned to gray, to the soft, dry color of a plant mysteriously nourished on the rocks.

This is David’s doing. He left it there, in the sun.

Stella’s words have come true. This thought will keep coming back to her—a pause, a lost heartbeat, a harsh little break in the flow of the days and nights as she keeps them going.

“Photography,” Bazin wrote, “affects us like a phenomenon in nature, like a flower or a snowflake whose vegetable or earthy origins are an inseparable part of their beauty.” But even he did not have in mind so thoroughgoing an act of writing by light, of revision by Nature, that transforms the supposed “lichen” (the human form, with its thatch) into something natural indeed: “a plant mysteriously nourished on the rocks.”

Is the photograph’s redemption also its relibidinization? “Stella’s words have come true,” we are told. By their capacity to transform—and thereby to produce a substitute, rather than the thing itself—the photograph and Stella herself are returned to nature’s “flow.” (Recall Bazin on the Egyptian mummy–strange precursor of the photograph: “To preserve, artificially, his bodily appearance is to snatch it from the flow of time, to stow it away neatly, so to speak, in the hold of life.” Stella, in contrast, does not merely return to the flow of days as, in an almost mythical aggrandizement, “she keeps them going.” ) In a truly Romantic synthesis, we find here a collaboration of nature and language, of word and sun, such that the photograph, no longer a mummification of sex, is restored to tenacious life. We must accept this, I think, in some limited way, as we accept the transformation—the return from death, though not rejuvenation—of Hermione at the end of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale: in that wondrous way of art that both “mends nature” and “itself is nature.”

Yet the full pathos of the scene depends, I think, on some lingering sense shared by Munro with Bazin, that the photograph is its object. As if by sympathetic magic, the lost girl, figuratively dead, amputated of all else save her incensing sex, is here restored to that flow, however stony and impersonal, of Wordsworth’s “A Slumber Did My Spirit Seal,” “rolled round in earth’s diurnal course / With rocks and stones and trees.” Or, for that matter, think of Rilke’s “Orpheus. Eurydike. Hermes.,” in which we learn that the lost Eurydike had

come into a new virginity and was untouchable; her sex had closed like a young flower at nightfall… She was no longer that woman with blue eyes who once had echoed through the poet’s songs, no longer the wide couch’s scent and island, and that man’s property no longer. She was already loosened like long hair, poured out like fallen rain, shared like a limitless supply. She was already root.

Munro’s Orpheus, unlike Rilke’s, is not greedy of possession. It is Stella who, accidentally on purpose, and despite her name’s suggestion of starry eternity, collaborates with nature to quicken the object world into life.

—Paul Franz

That Bazin judges “duplication” to be a false aim for painting can be seen in his comments on perspective drawing—itself, as he shrewdly notes, already in some sense a form of mechanical reproduction: “Perspective was the original sin of Western painting. It was redeemed from sin by Niepce and Lumiere.”

Marianne Micros, “Et in Ontario Ego: The Pastoral Ideal and the Blazon Tradition in Alice Munro’s ‘Lichen.’” In Robert Thacker (ed.), Critical Essays on Alice Munro (Toronto: ECW Press, 1998): 44-59.

Such is Christian Lorentzen’s view in his well-known takedown of Munro in the London Review of Books. In what promises to be an epochal essay in Munro criticism in the forthcoming issue of Literary Imagination, of which I am the editor,

(alias James Tussing), gives us reasons for taking a different view.

Really enjoyed this. Tarkovsky’s idea of film as “sculpting in time” is also relevant here:

“I see it as my professional task then, to create my own, distinctive flow of time, and convey in the shot a sense of its movement—from lazy and soporific to stormy and swift—and to one person it will seem one way, to another, another. Assembly, editing, disturbs the passage of time, interrupts it and simultaneously gives it something new. The distortion of time can be a means of giving it rhythmical expression. Sculpting in time! But the deliberate joining of shots of uneven time-pressure must not be introduced casually; it has to come from inner necessity, from an organic process going on in the material as a whole.”

Very very well done, and I say that while being more or less antagonistic at most every juncture. Some of my disagreement is principled, though I suspect it is mostly age, or sensibility, or a sense of the demands of the day and the temptations to which writers (and photographers) are prone. Maybe I'll find time to respond, though outlook is not promising. For now, provocative in the best way. Highly recommended.