John Ford’s American Justice

I thought I understood how art affects us—being an artist myself—until I discovered John Ford. He was the film director who invented the persona of actor John Wayne and crafted the myth of the American West. Growing up, when my dad played his movies constantly; I just knew them as John Wayne films.1

I had assumed that John Wayne was simply typecast, that his persona surfaced in the same unpredictable way that any given personality comes into existence; I assumed that the myth of the American West was formed through cultural evolution, not intelligent design. As I revisited Ford’s films, however, I realized that his cinematography was my earliest, most persistent exposure to visual devices like chiaroscuro lighting and the composition of romantic landscapes, which have determined my own approach to drawing. A single man shaped all of these crucial and varied parts of who I am; my beliefs about honorable masculinity were tied to my love for my father and his aspirational self; my dearly held patriotism; my sensibility as an artist, to which I have devoted my life—and thus discovering John Ford feels like beholding the face of God.

I didn’t know that an artist could become like an interventionist God. And it’s not just me. While discovering John Ford, I’ve also found other women who conflate the John Wayne persona that Ford invented with their own fathers. As I read Nancy Schoenberger’s 2017 book Wayne and Ford: The Films, the Friendship, and the Forging of an American Hero, certain autobiographical details unsettled me:

John Wayne particularly resonates with me. You might call it my “John Wayne problem.” You see, I grew up with men like Ford and Wayne; not only did my father look like John Wayne, but as a career military officer and a test pilot he lived the code of masculinity that John Ford and John Wayne created and embodied throughout the films, especially the Westerns, they made together. We all know that code, because, for good or for ill, it shaped America’s ideal of masculinity, what it means to “be a man”: to bear adversity in silence, to show courage in the face of fear, to bond with other men, to put honor and country before self—in three words, “stoicism,” “courage,” “duty.” John Wayne came to embody those virtues on-screen, and men like my father embodied them in life. …

What men like my father knew of America, they learned, in part, from John Ford. What they knew about being men, they learned from John Wayne.

I could have written that passage. My father looks so much like John Wayne that if I didn’t know for sure that was a picture of Wayne, then I’d swear it was my dad. My father was a career military officer in the U.S. Air Force. My father learned what it meant to be a man from watching John Wayne. And Shoenberger explains that there’s an entire niche of women who share our admiration:

As a fan of Westerns, I’m not alone among women. And despite historian Garry Wills’s observation that “It is easy to see why so few women are fans of John Wayne,” a handful of women writers have written encomiums to the stoic, sometimes bullying, sometimes tender archetypal hero embodied by Duke Wayne; writers such as Joan Didion, film critic Molly Haskell, and New York Times columnists Maureen Dowd and Alessandra Stanley have described their appreciation of Westerns and of one Western star in particular: John “Duke” Wayne, born Marion Morrison in Winterset, Iowa, in 1907.

“When John Wayne rode through my childhood, and perhaps through yours, he determined forever the shape of certain of our dreams,” wrote Didion in 1965 after visiting the set of The Sons of Katie Elder, a Western starring Wayne directed by Henry Hathaway. … In a piece titled “John Wayne, a Love Story” for the Saturday Evening Post, she recalled the first time she saw Wayne on-screen, in the summer of 1943: “Saw the walk, heard the voice. Heard him tell the girl in a picture called War of the Wildcats that he would build her a house ‘at the bend in the river where the cottonwoods grow.’” That line of dialogue has haunted her, she writes, a bit wistfully; it is “still the line I wait to hear.”

When John Ford invented the John Wayne persona and crafted the myth of the American West, he tapped into an ideal cherished by one of America’s largest and oldest subcultures: the Scots-Irish, also known as the Borderers.

John Wayne was Scots-Irish, as were many real-life cowboys. So is my dad. Every John Wayne character is a variation on the same Scots-Irish ideal of manly virtue that guards both honor and autonomy jealously. He neither delights in killing nor shies away from it. He’s a straight shot after any amount of whiskey.

I prefer the term “Borderers” because it’s less confusing. Growing up, when my dad told me that we’re Scots-Irish, I assumed some subset of Scots and Irish intermarried enough to become a distinct group. He never regaled me with stories of our heritage, so I didn’t learn the far more interesting and tragic Borderer backstory until stumbling across it well into adulthood—much as I stumbled across the auteur director John Ford.

My experience is probably shared with most Americans who grew up hearing that they’re Scots-Irish. Over the centuries, the Borderers endured poverty and violence, without much of an intellectual tradition to preserve or stories to pass down in a way that would create a sense of shared history. By the time they crossed the Atlantic, the Borderers were eager to embrace identities as simply American, without dwelling on what came before.

Historian David Hackett Fischer wrote a definitive account of the Borderers in his 1989 tome Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America. The four folkways represented distinct groups that initially seeded American culture in the British colonies: the Puritans, the Cavaliers, the Quakers, and the Borderers.2

Their history begins on the border where Scottish and English kings waged war for about 700 years. Fischer writes that “from the year 1040 to 1745, every English monarch but three suffered a Scottish invasion, or became an invader in his turn.” Both armies pillaged the unlucky villages on either side of the battle lines, while outlaws and strong men thrived by exploiting the chaos. Those villagers developed an extreme propensity for becoming stubborn, drunk, violent, and wary of outsiders, traits that over the centuries seemed to thicken like callouses to blunt the pain.

By the time the Scottish and British kings stopped committing atrocities in the borderlands, the abused Borderers had hardened into a bellicose and ungovernable culture. Fischer describes how they became “some of the most disorderly inhabitants of a deeply disordered land.” Meanwhile, the crown tried to “squeeze every cent out of the poor Borderers, in the hopes of either getting lots of money from them or else forcing them to go elsewhere and become somebody else’s problem.” Many went to Ulster in Ireland, where they picked up the other half of the moniker “Scots-Irish,” until the Ulsterites also tried to get rid of them. The Borderers finally made their way to America, and when none of the established colonies could stomach their ways for long, they settled in the Appalachian Mountains, away from the burgeoning American civilization. Later on, they pushed into the Southern and Western frontier, where cattle rustling came as naturally as it had to their forebears who reived along the Anglo-Scottish border.

After centuries in America, the Borderers have helped shape our culture at large. Thomas Sowell traced how they affected American black culture in particular, in his 2005 book Black Rednecks and White Liberals. He is sympathetic, but does not mince words about the “whole constellation of attitudes, values, and behavior patterns that might have made sense in the world in which they had lived for centuries, but which would prove to be counterproductive in the world in which they were going — and counterproductive to the blacks who would live in their midst for centuries before emerging into freedom”:

In this world of impotent laws, daily dangers, and lives that could be snuffed out at any moment, the snatching at whatever fleeting pleasures presented themselves was at least understandable. Certainly prudence and long-range planning of one’s life had no such pay-off in this chaotic world as in more settled and orderly societies under the protection of effective laws. Books, businesses, technology, and science were not the kinds of things likely to be promoted or admired… Manliness and the forceful projection of that manliness to others — an advertising of one’s willingness to fight and even to put one’s life on the line — were at least plausible means of gaining whatever measure of security was possible in a lawless region and a violent time.

Note his comparison to the culture of the Borderers:

The cultural values and social patterns prevalent among Southern whites included an aversion to work, proneness to violence, neglect of education, sexual promiscuity, improvidence, drunkenness, lack of entrepreneurship, reckless searches for excitement, lively music and dance, and a style of religious oratory marked by strident rhetoric, unbridled emotions, and flamboyant imagery. … Touchy pride, vanity, and boastful self-dramatization were also part of this redneck culture among people from regions of Britain “where civilization was least developed.”

When Scots-Irish research their heritage, they seem prone to romanticizing these tendencies. JD Vance is the most prominent example, who in his 2016 autobiography Hillbilly Elegy bragged about his family relation to the infamous Hatfield-McCoy feud between two Borderer clans in late-19th-century Appalachia. Another American politician, former Senator Jim Webb, wrote the 2005 book Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America, in which he prophesized the current American political landscape:

America’s elites have had very little contact with this culture. ... But they ignore them at their peril. Because in this culture’s heart beats the soul of working-class America. These are loyal Americans, sometimes to the point of mawkishness. They show up for our wars. Indeed, we cannot go to war without them. They haul our goods. They grow our food. They sweat in our factories. And if they turn against you, you are going to be in a fight.

Tom Wolfe called Born Fighting “the most brilliant battle flare ever launched by a book.” Twenty years after publication, it reads as a prescient interpretation of MAGA as a Borderer cultural movement aiming to take over the mainstream. Many proud MAGA populists admire President Trump as a “fighter” ready to retaliate against their enemies in the tit-for-tat style characteristic of Borderer feuds. Journalists constantly quote Trump supporters to this effect, and these interviews are backed by the data. Exit polls from the last Republican presidential primary found that in every state polled, Trump overwhelmingly won the voters who said they were looking for a candidate who “fights for people like me.”

This Borderer cultural movement hasn’t resulted in a John Wayne renaissance. His cowboy persona might be the best kind of man that Borderer culture could muster, but most Scots-Irish men don’t resemble John Wayne. The hard truth is that the Borderers found their niche in America, in part, because large numbers of pugnacious men were quite useful for attacking Indians on the frontier or fighting redcoats during the Revolution. When my dad joined the Air Force — a common avenue of upward mobility among the Scots-Irish, where military discipline and codes of conduct can tame and channel Borderer truculence — he was put to use in the Middle East beginning with the Gulf War and then in Afghanistan and Iraq after 9/11. Quite a few Americans with Scots-Irish heritage became generals and presidents, Andrew Jackson chief among them, while many more became bullet bait.

But the Borderer cultural niche shrunk once Americans tamed the frontier, and then contracted again once we grew wary of “forever wars.” America has fewer uses for pugnacious men nowadays—although MAGA may be finding new outlets for aggression through the Department of Homeland Security and ICE recruitment. When I watch videos of ICE and other DHS agents using excessive force, I wonder how many of these men were touched by Borderer culture and its broader influence on our country. It would be a poignant historical development if the descendants of people savaged in the Anglo-Scottish borderlands have become the most brutal enforcers of American borders.

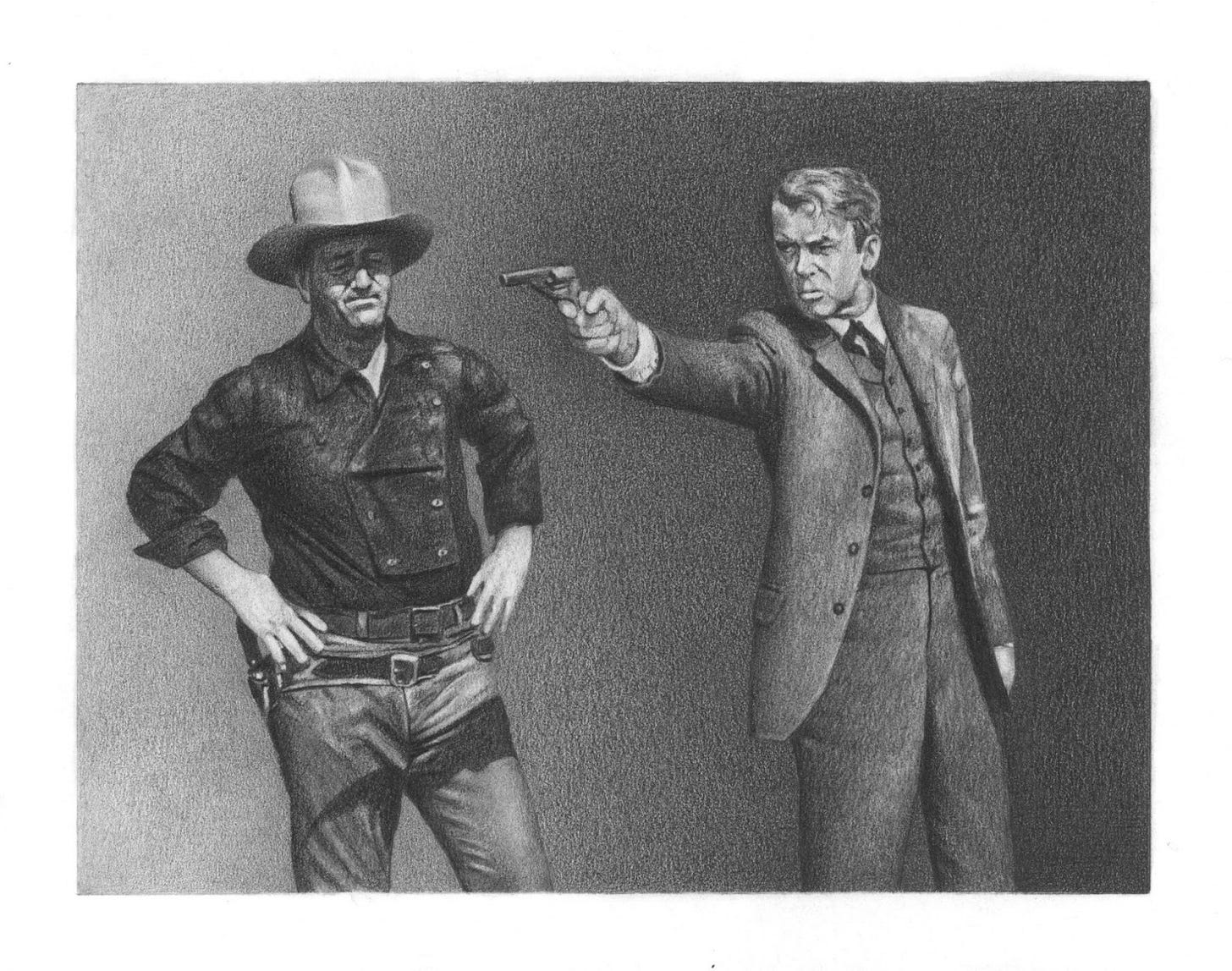

In what is widely considered John Ford’s last great Western, his 1962 film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, the auteur demonstrates why even the best Borderer ideals must be laid to rest. The film shows how two countervailing types of justice shaped American culture. John Wayne, of course, represents the Borderer style of justice.

The other type is symbolized by Jimmy Stewart’s character, Ransom “Ranse” Stoddard, a lawyer from back east who doesn’t know how to handle himself out west; Wayne’s cowboy character Tom Doniphon both protects and antagonizes Stoddard. While the lawyer believes in the rule of law, the cowboy scoffs at the law’s impotence. For in the frontier town of Shinbone, the government is far away and the marshal is a coward and a slob who lets the outlaw Liberty Valance run roughshod over the locals.

Stoddard wants to prosecute Valance and instill a love of civic virtue in the townsfolk. When Stoddard begins a school to teach them how to read, he focuses more on civics than on phonics. Doniphon warns Stoddard that “I know those law books mean a lot to you. But not out here. Out here a man settles his own problems.” He tries to teach the gentlemanly lawyer how to shoot and prepare to fight dirty, but Stoddard is ideologically opposed to extrajudicial justice. He answers Doniphon, “Do you know what you’re saying to me? You know you’re saying just exactly what Liberty Valance said. What kind of community have I come to? You all seem to know about this fellow Liberty Valance, he’s a no-good, gun-packing, murdering thief. But the only advice you can give to me is to carry a gun. Well I’m a lawyer!”

Though Stoddard does start carrying a gun just in case, he never learns how to use it. In the final showdown — one of those classic Western revolver duels, with two men facing each other down on a Main Street lined with false front façades and swinging saloon doors — Doniphon saves Stoddard’s life and lets him take the credit as a local hero: “The man who shot Liberty Valance!” Doniphon gives up glory; Stoddard gets the girl. The cowboy saves the lawyer’s life twice in the film, and both times, he brings the battered gentleman to his love interest, Hallie, who falls for Stoddard while nursing him back to health. Doniphon never tells Hallie who really shot Liberty Valance.

The jubilant townsfolk elect Stoddard as their delegate to Congress in their petition for statehood, which propels him to a prestigious political career, while Doniphon burns down the house he built for Hallie. Decades later, Stoddard and Hallie return to Shinbone for Doniphon’s funeral, where the undertaker has stolen the dead man’s boots and put him in a plain, wooden box. Doniphon’s old ranch is still charred because he never bothered to rebuild it. After they lay Doniphon to rest, on the train back east, the conductor excitedly tells Stoddard about all the special accommodations he made to ensure the train gets him back to Washington in record time, because “Nothing’s too good for the man who shot Liberty Valance!” The film ends with Stoddard scowling at his pipe while Hallie stares wide-eyed out at nothing.

They know that Doniphon is the hero in their story. Though Stoddard long ago accepted Doniphon’s case, he still looks troubled by the fact that his values — that justice demands we give men a fair hearing before executing them, and that we should revere the laws that restrain violence enough to make justice possible — were toothless pieties out on the frontier, far beyond the reach of the leviathan of government, and that the strength of a mostly good yet morally ambiguous man like Doniphon — a man who was unperturbed to become judge, jury, and executioner — was needed to establish the rule of law on the outskirts of American civilization. And Hallie appears haunted by the possibility that, despite outward appearances, she married the lesser man.

Doniphon’s brand of justice is entwined with a sense of personal honor and the amount of violence necessary to uphold it. His strength and resourcefulness make him the only character in the film who proves capable of choosing an outcome. Stoddard lacks the capacity, despite his courage, to effectively bring the law to bear in a place where no one has a monopoly on violence.

The way justice is dealt within civilization cannot apply to the frontier, where “might makes right.” The people of Shinbone were lucky that the mightiest man around also happened to have an ounce of goodness in him. Stoddard would say that this means there could be no real justice on the frontier, and he’s probably right — maybe that’s why a man like Doniphon would sacrifice everything to help establish the rule of law.

In America, the rule of law has a spiritual component. Renowned sociologist of religion Robert Bellah took to calling this the “American civil religion,” a phrase he coined just a few years after The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance came out in theaters. His characterization aptly describes how much we cherish the symbols and values enshrined by America’s founding myths. Patriotic hearts swell when Americans recall Jefferson’s lofty language in the Declaration of Independence about our God-given rights, and documents like the declaration and our Constitution are enshrined in the National Archives as sacred relics. Our country has no common race or religion, and we are instead meant to be bound together by a shared devotion to liberal democracy.

Stoddard was a passionate believer in this religion, and derived his sense of justice from it. He taught the townsfolk in front of the American flag and a portrait of George Washington, while Abraham Lincoln’s visage hung on the other wall, surrounded by candles like an altarpiece. Though the point of his lessons was allegedly literacy, Stoddard explained that “we’ve begun the school by studying about our country and how it’s governed.”

At the same time, Americans have glorified the cowboy who lived outside the very system of laws we worship. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance justifies such heroes in the American story as necessary precursors to our beloved legal system — tough men for tough times, who broke the eggs that became our omelet. But now that we have our omelet, such men can become malcontent liabilities, with no useful outlet towards which we can channel their strengths.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance takes place when the frontier was nearly tamed. The townsfolk in Shinbone wanted to draw borders around their territory by pursuing statehood, so that the rule of law could protect them. They no longer wanted to live and die by the sword (or the gun) in an unforgiving honor culture, in which status and safety depend on a reputation for retaliating violently against even minor slights. In the film, it was necessary to give up Borderer-style culture in order to draw borders, as symbolized by Tom Doniphon’s sacrifice. His pitiable end — bootless in a box, with no family to mourn his passing — suggests that there was no place for such a man once the town turned its back onthe culture that formed him.

John Ford crystalized what it meant to be an American man in the persona of John Wayne, and then in his last great Western, he showed us why that kind of masculinity necessarily became obsolete. Now it seems that Americans are floundering within that obsolescence. In his recent essay “Masculinity at the End of History,” Matthew Gasda writes that:

Men in our society, especially young men, are in the position of not knowing who they are, what they want, or how they are supposed to live, and of being, in an anthropological sense, exampleless. The cliché of American masculinity, widely disseminated in the academy, is that masculinity is in a crisis. This is the exact inverse of the truth. Masculinity is desperate for a crisis. It is docile, unsure, and formless. At most, it is at the germinal phase of crisis, lacking a catalytic agent to propel it to its full-blown state, which at least can be registered and reckoned with. After all, crisis implies that something is happening, that something is at stake. The uncatalyzed proto-crisis, or the noncrisis, of American masculinity is repressed, unexpressed, yet omnipresent.

To which Gasda adds, in a suggestive aside:

The proto-crisis exists in the first place because tradition has been replaced by representation. Instead of learning from fathers and grandfathers and brothers, from coaches and teachers and priests and pastors, the American male learns from watching images on screens: films and television have been playing the role of surrogate father for a long time now, but at least those media tended to have forms, arcs, and archetypes. Today’s privileged mediatic forms—five-second clips, parasocial personality brands, algorithmically constructed collective identities—do not have even that.

If Americans can’t help but learn how to be men from watching images on screens, then more of us should discover John Ford. He gave us an example of masculinity after John Wayne in the figure of Ranse Stoddard. Ford shows us that this is not an easy solution, and that it requires sacrifices from men and women alike. Men like Stoddard doubt themselves, and women like me will wonder how we could possibly admire and desire their diffidence as much as the potency of men like John Wayne. I worry that this is an impossible task, but, then again, John Ford could craft an archetype of American masculinity like nobody else.

Recently, someone told me that talking about Wayne without talking about Ford is like discussing Lisa del Giocondo with no mention of da Vinci. I hadn’t realized that most of the John Wayne films I grew up with were directed by one man.

Of the four, the Borderer immigration wave was by far the largest, numbering about 250,000—for comparison, the Puritan wave that most remember as more central to the American story only numbered 20,000.