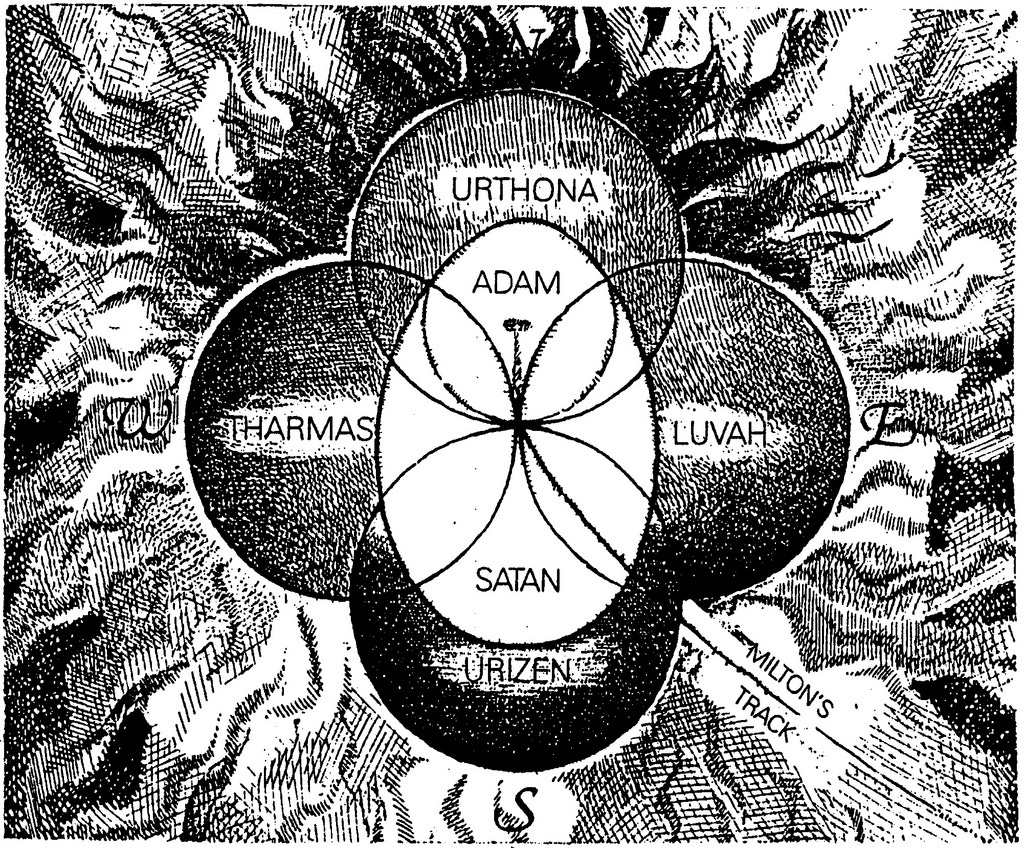

Four Zoas

Gasda. It is important to remain dialectical with movements, brands, signifiers, and historical genealogies. And, I think that, Romanticon has done a decent job, this year, of scattering conceptual seeds in different places in order to produce different intellectual hybrids (the con in Romanticon suggests retrenchment, slowness, and yes dialecticism, tradition, and smallness or localism). And this work is just beginning. Here’s the paradox as far as I see it: Romance is one thing and it can only be experienced in the soul as the soul with other souls. Embodied souls. Romanticism is a multimodal set of ideas across languages, times, cultures that can help frame, prune, and instigate romance. But it’s not romance. And so here we are trying to distinguish between Don Quixote’s values and the books he read, between his adventures, his embarrassments, and his ultimate resignation; between Quixote’s courage and Quixote’s foolishness. Between Quixote’s cowardice and Quixote’s perseverance. Between Sancho’s wit and Sancho’s remorseless stupidity. So what is the paradox of four editors and dozens of writers and thousands of readers and millions of app users? Well it’s that romance is always personal, always for the self and by the self. And always sui generis and heterodox of its core. Always taking place in the fascinating territory of the absolute moment (which is off-limit from academics and from the ultra-right and the ultra-left and the ultra-center; and from government pressure and theological pressure and philosophical pressure and critical pressure). I’ve enjoyed working on Romanticon, not because I know, or like the pretense of knowingness, but because I like to think, and take weird paths and ‘wrong’ turns. As a “romanticon” I am my own Sancho to my own Quixote; and as editors we are Sanchos to our own Quixote sometimes, to the writer’s Quixotes (because the writers sometimes are the Quixotes to our Sanchos); and because sometimes we are the Kierkegaards to our own Hegel’s too; and the Hegel’s to our own Kierkegaards (systemizers and anti-systemizers)). We’re all falling asleep and waking up at different times. It can be very painful to sleep through the test and be awake for a long time during the time of night when one should be dreaming; this is the difficult work of being a historical subject, of having to speak in mutilated digital forms and mutilated hysterical times. Thus, I could see Romanticon going further into the Gnomic in the next year and drawing more, so to speak, with the right side of the brain. There are theories of what things are or were, but there are also experiences which must be transcribed and made sense of. This is the American tradition of Emerson, Dickinson, Stevens, Cavell. It’s the German tradition of Hölderlin, Nietzsche, Heidegger. It’s the French tradition of Hugo, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Proust. It’s the English tradition of Blake, of Tennyson, of Lawrence. And maybe it has always been through the tradition of Italian and French writers, of Catholic literature. A poet’s energy must be spent in a kind of re-seduction of their own mind. Otherwise, the poet’s powers are drawn elsewhere and lose their charge. It’s strange to say, but the strength of a poet and of a philosopher comes from the strength of giving birth to themselves (taking pleasure in the procreative relationship between mind and soul).

Willman. While Romanticon is a project that takes pride in the rigor and pleasure in the challenge of describing the long and complex histories which make Neoromanticism and New Sincerity legible to different areas of collective life and thought, I nonetheless have experienced the cracks between each description take me away from, and yet propel me back towards the source of conviction that comes prior to the explanations.

Making legible is a day time experience, it is idea-management, knowing layered-up with thought. But as each successive author ties the ideas up so all the concepts are managed, and the matter seems settled and quiet, and thus finally put to bed, I find the quiet heart of the Romantic emerges in the abeyance of confusion. If we have repeated any issue here, it has for me had the effect of washing Romance clean of all her sounds and symbols, until I am just with her, the quiet soul of romance, the part of it which can really be Written. Here I find knowing, the philo of philosophia—knowing that more thought is necessary—which must come before every great question, and which makes the answers to them something we can recognize.

I don’t understand how anything can really be written during the day.

Before midnight all production of text is just letter-management. It isn’t till a certain quiet sustains, that the part of you which can actually write has any hope of emerging. In the day time everything buzzes and everyone is all layered-up: layered in tasks, layered in roles, layered in too many awarenesses—the day of the week, prediction models of the thoughts of others, things left undone, things not yet done, things done wrong. I’m not sure why, but I am sure that at night the world achieves a radical stillness and for those who can bear it, a chance to slip out of all their layers and stare openly at the world as it lay.

These are the most romantic moments of my life. Up at night alone, with a mind made new by ideas and trying to remake everything around me in its image. Or lying in bed next to a lover, whispering quietly things that could never be said upright. Out on a prowl, glued in a pack, looking for trouble and the chance at seeing under the edges of one another’s peeling personalities. These moments when we find ourselves and one another a little more alive and more real, which is to say a little more fictional and a little more storied.

After the last few months of reading the works published by our outlet, ingesting new angles, new genealogies, of what Romanticism is and where it came from, what its value is. I went from being reasonably sure I understood what it meant to be a Romanticist to finding myself watching 12 minute YouTube videos—introductions to Romanticism directed at first year art students.

The more one thinks about something the further it recedes—in this way, I often feel like Architecture, despite being an architect myself, is the thing I know least about. At some point this project has likewise mystified Romance for me.

What even is it? It was as though we were constantly repeating the word out loud; Romance, romance, RoMance, row-mance, roman-sse; until the meaning falls away and there’s only sound and an empty puzzle of symbols—suddenly the thing is a million other things, and the over-conceptualized reference becomes utterly useless as a word; canceled out in repetition. Until all I have recourse to is the memory of it; moments which I can only describe as romantic.

The inexhaustible romance of experience.

I am romantic. If I didn’t break with the day, part with the will to identity—so intensely different from discovering and becoming self—and allow the components of my life bleed back into an original whole, then I would simply have no clue what the poets were talking about. And yet I do know.

When Kerouac’s protagonist proclaims “we know what IT is and we know TIME”, I do know It, and I do know Time. I know just what he means even if neither he nor I could articulate it any more literally than that. I know because I too have prowled around, drunk and high, with my sensitive-type friends, talking in manic rhythms until we have discovered some fundamental truth to the universe receding and receding away from the sunset as too the sunrise.

And when D. H. Lawrence laments about what is sold to the bitch-goddess, Success, through the industrialization of the human spirit, even I—who has been born long after the almost complete industrial patterning of every moment of human life—understand the subtle and yet sublime “unravished” wild which makes a human properly so. I know because I’ve stayed up at night and watched the galaxy tilt across the sky. Because I’ve dipped my soles and toes in a star-filled lake while frog-song saturates the air, waves which I pull in and out of my body like a tide. Because in such moments, when I have bled back into earth’s nesting rhythms, I’ve found myself returned, completely natural, without any effort—so unlike the constant effort required to live culturally.

Franz. I too write during the night, though my nighttime has become, by and large, the early morning. “Night is for those who believe life holds an indefinite, possibly infinite expanse,” I jotted once, scattering casual coin, “the morning is for those who know life’s finitude.” Once I believed in the former, now know the latter. And yet. There is a form of very early rising, a rising not to meet the day but to steal some secret sweetness from what comes before it, where the infinite lingers. Patches of infinity, cast off by the receding tide. What then have nighttime to do with daytime thoughts? I think of some Bob Dylan lines I’ve long admired—for their unemphatic inversion of expected sequence: “I wonder if she remembers me at all / As many times I’ve hoped and prayed / In the darkness of my night / In the brightness of my day.” Darkness preceding brightness; night, day: does this not suggest the dream, the cherished after-image, that must somehow be carried forward as a secret charge? From Wordsworth, we know the risks. Inheritances of the infinite “fade into the light of common day.”

There comes before my mind something crystalline, diamond-hard, infinitely determined. It is the bit of a drill: turning, turning, digging down through the day from night to night, threshold to threshold. Crystalline and infinitely fine: a poem. And it is true, I have long thought of a poem in terms of figures of endurance. Poems are “strongholds in imagination,” as the English poet Geoffrey Hill once put it, lifting Wordsworth out of context, building impregnable “castles in Spain.” But I think, too, of an image from Paul Celan, German-language poet and Jewish negative theologian, who imagined the poem sometimes as a “handshake,” but also, in the image I have preferred, as a “breath-crystal”: afflatus of life frozen, transfigured, made alien.

(Was it something like my drill that Celan had in mind when he wrote, in prose: “A poem lays claim to eternity, it seeks to reach down through time, but down through it, not over it and away”?)

A Modernist thought more than a Romantic one, perhaps, or a Modernist as much as a Romantic one: a sense of the poem as something tactile, object-like, stranded among a tide of utilitarian objects. Something akin to the figure Celan uses in his translation of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 5: Doch so, als Geist, gestaltlos, aufbewahrt, | west sie, die Blume, weiter, winterhart: ‘But so, as spirit, shapeless, stored away: | It lasts, the flower, further, winterhard.’

Nothing more encapsulates the difference between Celan’s translation, with its crystalline final word—hardened by winter, hard as winter, the bit of the drill biting recalcitrant rock—and its original, the most dramatic and arresting of the “generation sonnets” that open Shakespeare’s collection. Sonnet 5 indeed combines the exhortation to biological generation with an image of something inorganic, something we might associate with a poem. Yet notice the difference in emphasis: “But flowers distilled, though they with winter meet | Leese but their show, their substance still lives sweet.”

Celan’s poem flips the tenor and the vehicle of Shakespeare’s original. Generation, in those strange early Sonnets of Shakespeare’s, becomes propagation of the self—minting its copies—and can be likened to a poem, so conceived. For Celan, however, the poem is seemingly left without conveyance. (Contrast Horace’s non omnis moriar, ‘I will not altogether die’, his version of the infinity claim that haunts Shakespeare’s Sonnets, with its realistic sense that he will live “for as long as the pontifex maximus ascends the hill with the quiet virgin”; that is, for as long as there are those who know his language—though in fact the language has outlived the pagan priest.)

Celan, of course, had his reasons. Yet I am struck now by the thought that the modernist fantasy—however enforced by circumstances, and, in its resistance to them, adamantine, heroic—to decouple artwork and conveyance; of the poem as pure crystalline endurance, waiting for its impossible readership, is in some ways as mad as that of the early Latin poet Gnaeus Naevius who imagines his language dying with himself: Inmortales mortales si foret fas flere | flerent divae Camenae Naevium poetam. | itaque postquam est Orcho traditus thesauro | obliti sunt Romae loquier lingua Latina (‘If it were fitting for immortals to lament mortals, the divine Muses would mourn the poet Naevius. And how that he has been handed over to the treasury [the ‘thesaurus’] of Death, the people at Rome have forgotten how to speak the Latin language’). No poet of sense wishes utterly to ruin his own language; no poet of sense hopes for no means of conveyance.

(Paul Celan had, incidentally, a son, Eric: a juggler—and, latterly, a keeper of his father’s and his mother’s Gisèle Celan-Lestrange’s memories.)

Romantic, today, might be to find a way to rejoin the impulses of Celan’s translation and its original, winter crystal and spring song.

Day, today, is winter. These slumberous night-thoughts are wrapped in their own pelt.

Galluzzo. It took a pandemic and a years-long retreat into the woods to give me space and time enough for the writing that finally became my (much truncated) first book. Although I’d been offered a book contract with an academic publisher several years before, I’d abandoned the idea of a scholarly monograph by this point in 2020. My ideas and fixations old and new—on Romanticism and the ecological sensibility that grew in the ruins of the orthodox Marxist modernism that had shaped my outlook for the previous fifteen years — nevertheless stayed with me and continued to drive my writing, despite its strange and seemingly ludicrous subject matter. John Boorman’s Zardoz—a cult film that has fascinated me since I first saw this psychedelic curiosity in high school under the, in this case, superfluous influence of drugs—offered a vehicle to grapple with questions that began to preoccupy me at the time. For example, human finitude and contingency or their political consequences, as I wrote in the coda to the book:

We are born, live, and die in time, as both products and makers of our times. We persist beyond the span of an individual life in the form of our collective arrangements and traditions. The “birth of new men and the new beginnings” ensure both the continuity of those traditions and the possibility of ruptures or revolutions. 1

So much of my subsequent embrace of Neo-Romanticism—mining the historical Romanticism of Wordsworth and Blake on the one hand, and Novalis and Schelling on the other—stems from my recognition that the first Romantics saw in corporeal life and natural world the spirit or mind typically counterposed—in the orthodox Christian tradition and its secular proxies—to a fallen or imperfect physical reality. The Romantics also understood, at the dawn of the industrial capitalist era, that reductionist materialism and its complementary quantification of the lifeworld are inextricably entangled with a historically novel will-to-power—later theorized as alienation, rationalization, and reification—that threatens earth and human being: both interdependent forms of incarnate spirit. More so than the old-time religion excoriated by Enlightenment and its apostles, the Promethean urge to dominate the natural world and “perfect” the human creature presented—in 1818 to the author of Frankenstein—the more pressing threat: a new and disastrous form of idolatry to be administered by an emergent technocratic priesthood.

There is a radical vision implicit in these various Romanticisms, stemming from what philosopher Charles Taylor names the desire for “resonance”: seeking communion and community among human and non-human beings under a new dispensation marked by fragmentation, alienation, and disenchantment of a particular sort. This vision unites the disparate and seemingly incoherent political tendencies that constitute this movement, from utopian eco-communism to traditionalist or conservative communalism. Despite popular caricature, Romanticism is anything but some expressivist cult of the self, at least insofar as we identify that self with the bounded bourgeois ego and its petty private impulses and interests.

Am I gratified? Several months after launching Romanticon, an online journal of romantic letters, Neo-Romanticism is on everybody’s lips. And there is also a lot of talk about embodiment and vitality as a specifically Neo-Romantic response to our disembodied digital condition. Romanticon co-editor Paul Franz identifies Romanticism—or is it Neo-Romanticism?—with vitalism, as he writes:

Romanticism rejects the triumph of the empirical; it continues to see the world in the light of desire. Vitalism—raging against the dying of the light—is a version of that same spirit. Both assert life against death. In a certain sense, this places the Romantic against “nature” (Emerson writes, of the “aboriginal self,” that “We first share the life by which things exist, and afterwards see them as appearances in nature.”) But empirical reality itself today is not nature; we have gone through the looking glass; our romantics live in cities.

Franz goes on to note that, for the Romantic:

death must be rejected in the right way. Transhumanist life extension is not Romantic. Why not? Because it makes the body itself the alienated object of technological manipulation. (And is, furthermore, mere prosaic perpetuation, without heightening.) Romanticism is to fight against death but to do so on the soul’s own steam. Hence the duality of its embrace of natural limits, even as it strains against these.2

But rather than some irresolvable antinomy, the Romantic embrace of limits is the acceptance of individual finitude—the gift of death that functions as precondition for individuality, as Hegel argues—while the Romantic rejection of death occurs on a collective level since we “persist beyond the span of an individual life in the form of our collective arrangements and traditions.” Too many exemplars of the present-day Romantic revival neglect the collective element of the Romantic tradition they invoke. I agree that vitalism—or, more precisely, pantheism—is a key ingredient in the Romantic worldview. But, more than an assertion of life against death (specifically in the form of quantification), the Romantics’ “natural supernaturalism” limns an immanent order in the cosmos from which we have been alienated, then strives to reconnect both individual and communal human life with that order.

The rejection of technological manipulation is nonetheless an important Romantic inheritance.Ross Barkan identifies this Luddite impulse—riffing on Franz’s definition of vitalism to argue that a new vogue for in-person literary gatherings in theme park downtown Manhattan represents a Neo-Romantic revolt against the Machine—with vitalism as such: “Of late, I’ve been thinking a great deal about vitalism. In our tech-swamped age, there’s been, among a certain number of young and middle-aged New Yorkers still interested in the written word, a rebellion.”3

I agree that embodied interactions are a good sign: a symptomatic longing for a less mediated being-together. Although rather than a new, or self-consciously Romantic turn, this phenomenon stretches back to the pandemic era: a youthful reaction to sheltering in place and an everyday life almost entirely subsumed by screen and algorithm. But good signs are not sufficient, and being-together against the algorithm should not be measured by the enthusiasm for or frequency of live events but the extent to which such events have been distorted by the digital hologram. When so many of these events revolve around “readings about explicit sexual acts,” in Barkan’s words, I don’t think we are witnessing intimations of some coming communion so much as a live-action OnlyFans letter—by e-girl, incel, and various other sorts of cyborg semi-subject—staged to be re-shared and Instagrammed. Eros-free exhibitionism, under which life and language are crammed into the contours of thirst trap and troll show, is more parody vitalism than the thing itself.

Romanticon co-editor Matthew Gasda and I at least partly envisioned Romanticon as one way of moving past a crass, and crassly predictable, downtown literary scene which—with its shock tactic porno pantomime and reactionary troll theatrics—mirrored, in straightforward and distorted forms, both the online culture and woke hall monitors that our new iconoclast-manqués pretend to reject. Drawing on a Romantic tradition that—in its combination of reverence and iconoclasm, tradition and novelty—offers us one of the few countercultural alternatives to modernity’s mainstream, we saw one possible exit route out of the culture wars and their fruitless see-saw movements from woke to anti-woke, this vibe, that vibe, then the first vibe again. How might we instead fashion another, still mostly inconceivable, politics and aesthetics for an age of collapse?

We are, I think, half-succeeding—at least insofar as the journal goes—as we knit heterodox religious thinkers, off-kilter eco-socialists, and all manner of storytellers into a crazy quilt of disparate perspectives united by the Romantic ethos described here, with each contributor proffering his or her own version of how to romanticize a rapidly disintegrating world. Yes, we are doing this online and by way of the hologram—a concession to “reality” with the aim of one day tearing it all down and building something anew: a meeting house in the forest high among the mountains. Here is an aspiration unlike most of what now gets lumped under Neo-Romanticism: this month’s trending buzzword.

Philosopher Frederick Gros describes the older Rousseau as no longer wanting

anything but forest paths. To be alone, far from the hubbub. No longer to have to check his social share price daily, calculate his friends, ration his enemies, flatter his protectors, ceaselessly measure his importance in the eyes of fops and imbeciles, return looks in kind, avenge words with words. He wanted to go elsewhere, far away: buried in the woods.

The libertine circus that was eighteenth-century European high society— in which Jean-Jacques certainly participated for a long time—ultimately drove him to the forest and the understandable, if overblown, notion that while human beings in a half-mythical state of nature are innocent, society is corrupt and corrupts. His society certainly was that: a rotten body that needed eviscerating from the head down.

And in the wake of that evisceration, Rousseau’s Romantic heirs—in their dreams of Pantisocracy if not real-life interpersonal relationships—saw in forest, as much symbol as place, not escape route but site for another kind of community. Writing from the woodlands of Northern Sweden among various writers and thinkers debating ends, beginnings, and how to begin after the end, a new Romanticism remains the great thing we must make in the new year.

The right hemisphere is more active in children up to the age of four years, and intelligence across the spectrum of cognitive faculties in children (and probably in adults) is related principally to right-hemisphere function. In childhood, experience is relatively unalloyed by re-presentation: experience has 'the glory and the freshness of a dream', as Wordsworth expressed it. This was not just a Romantic insight, but lay behind the evocations of their own childhood by, for example, Vaughan in The Retreat and Traherne in his Centuries. Childhood represents innocence, not in some moral sense, but in the sense of offering what the phenomenologists thought of as the pre-conceptual immediacy of experience (the world before the left hemisphere has deadened it to familiarity). It was this authentic 'presencing' of the world that Romantic poetry aimed to recapture. - Iain McGilchrist, The Master And His Emissary

Ahh! Happy New Year! Please give us the pleasure to read you on architecture